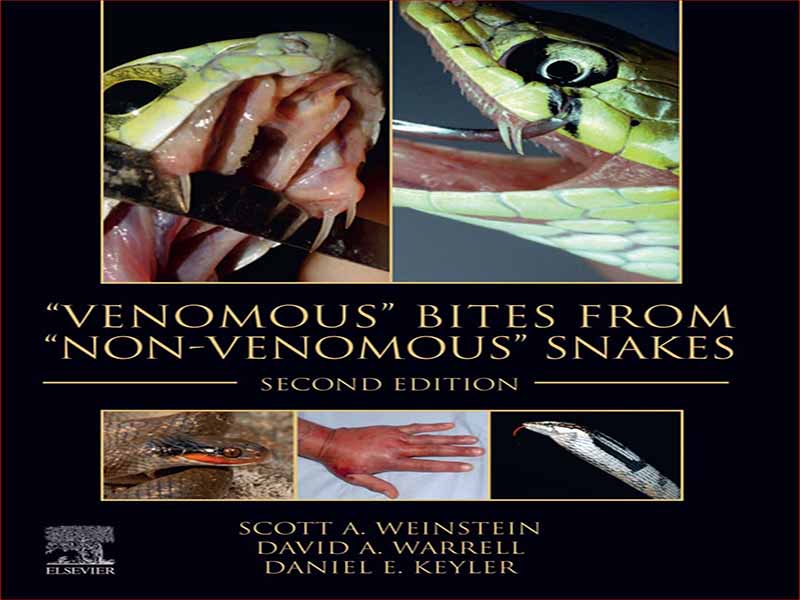

- عنوان کتاب: “Venomous” Bites from “Non-Venomous” Snakes

- نویسنده: Scott A. Weinstein

- حوزه: سم شناسی

- سال انتشار: 2023

- تعداد صفحه: 790

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 20.2 مگابایت

ترس و شیفتگی با مارهای سمی بر درک انسان از دین ، معنویت ، ماوراء طبیعی و پزشکی تأثیر گذاشته است. یکی از رایج ترین خطرات مربوط به سلسله های مصر باستان ، آسیب دیدگی مارها یا عقرب ها بود. بروکلین پاپیروس ، که در طول سلسله سی ام (380E343 پیش از میلاد) نوشته شده است ، آنچه را که ممکن است یکی از اولین معالجه شناخته شده شناخته شده به درمان مار باشد ، تشکیل می دهد. درمانها شامل عمارت ، تحریکات و طلسم ها با تمرکز بر تسکین قربانی “سم معنوی و جسمی” بود. بر خلاف اظهارات کاملاً نامه در مورد درمان مار در پاپیروس جراحی قبلی اسمیت از سلسله هجدهم (حدود 1550 پیش از میلاد) ، پاپیروس بروکلین شامل بخشی از شناسایی اسنک های سمی مهم پزشکی در نظر گرفته شده برای هدایت همبستگی است. به همین ترتیب ، در Triatise de Venenatis Animalibus Eorumque Remediis (بر روی حیوانات سمی و داروهای آنها) ، پزشک Philumenus اسکندریه (حدود 180 میلادی) از جمله بحث در مورد انواع مارهای سمی و علائم مربوطه و صداهای مربوط به بیت های آنها ؛ این کار ترجمه شده بعداً به نقش مهمی در لور پزشکی عربی در Snakebite بازی می کند (Walker-Meikle ، 2014). در مقابل با بسیاری از تحویل های معاصر ، برخی از سنت ها به طور خودکار تماس با مار را به عنوان ایجاد حوادث غیرقانونی اجتناب ناپذیر یا اثرات مخرب جسمی/معنوی مرتبط نمی کنند. در دوران باستان هند (تقریباً 100E300 CE) ، رشته های آیورودیس و تانتریک مار های بتونی را که منجر به تحریک (Savis _ A) می شود ، متمایز می کند و این کار را انجام نمی دهد (NIRVIS _ A). آنها ماهیت مترقی Envenoming جدی را به رسمیت شناختند و برای درمان اثرات مار که پس از عبور از پوست به خون به بافت های عمیق تری رسیده بودند ، مشکل زیادی را به وجود آوردند (Slouber ، 2016). در اوایل رنسانس ، کیمیاگر مبهم/گیاه شناس/اخترشناس/پزشک پزشکی ، فیلیپوس اورئولوس تئوفراستوس بمبستوس از Hohenheim1 (1493e1541 ؛ مشهور با معروف به محرمانه بودن رومی ، پاراس آزوت ، داروی معنوی انسان انسان است. موضوع مشترک در زیر اولین برداشت های بالینی از Envenomation و دیدگاه های دوم در قرون وسطی ، غالب بود. این مار که هم وجود معنوی و هم جسمی را مسموم می کند. اعتقاد بر این بود که اثرات سمی نیش های Viper به دلیل “ارواح خشمگین” است. اولین سرمایه گذاری سیستماتیک سم مار توسط پزشکان هفدهم ایتالیایی ایتالیایی (1626e1698) انجام شد. آزمایشی طبیعت سمی زهر مار ، رابطه ای بین قوطی ، وزن بدن و اثر سمیت سم در نزدیکی رگ خونی برقرار کرد. علاقه به پاتوفیزیولوژی و مدیریت بهبود یافته مار بر شخصیت بیشتر سم ها متمرکز شده است ، اما این کارل در سال 1938 نبود که کارل اسلاتا (1895e1987) و هاینز فرنکل-کانرات (1910E1999) در جداسازی یک سموم ، کروتوکسین ، از ورم ، از نظر کروتوکسین ، از نظر کروتوکسین. Rattlesnake یا Cascabel گرمسیری مهم (Crotalus durissus terrificus). بهبود در روشهای جداسازی بیوشیمیایی پروتئین و توصیف به سرعت دانش زهر را پیشرفت می کند و اغلب یک مبنای دارویی برای اثرات بالینی مشاهده شده در قربانیان مار های مهم دارویی فراهم می کند. تأکید دیپروپورینات تحصیلات تکمیلی زیرزمینی بر خصوصیات زهر زیستی مربوط به محوریت تحقیقات زهر را کاهش می دهد ، در بیشتر موارد ، بیشتر مارها را با ترشحات دهان و دندان از اهمیت پزشکی ناشناخته یا کمی شناخته شده به استثنای. یافته بسیار محدود به تحقیقات زهر مار ، دامنه تحقیقات را محدود کرد. مارهایی که دارای دندانهای فک بالا خلفی (“حصارهای عقب”) هستند و به ندرت باعث مرگ و میر یا عوارض انسانی می شوند ، تا حد زیادی نادیده گرفته می شدند. با این حال ، اگرچه این علاقه محدود به “زهر خفیف” یا “بزاق سمی” مارهای “عقب” منجر به تحقیقات پراکنده در مورد ترشحات شفاهی آنها شد ، اما مارهای پایان نامه اهمیت آنها را مشخص کردند. در اواخر قرن نوزدهم تا اوایل قرن بیستم ، چندین متخصص هراسی و پزشکان کنجکاو شروع به این سؤال کردند که آیا برخی از مارها به عنوان “بی ضرر” تلقی می شوند ، به عنوان مارهای هوگنوز (هترودون اسپپ.) و مسابقه دهندگان آمریکای جنوبی (Philodryas spp.) ، “خفیف سمی بودند. “” محققان آفریقای جنوبی شروع به گزارش موارد تهدیدآمیز از زندگی Boomslang (Dispolidus typus) Envenomation کردند ، و محققان آمریکای جنوبی مطالعات مربوط به زهر Philodryas را انجام دادند و خاطرنشان کردند که اثرات گزارش شده از بیت های آنها گاهی شبیه Vipers است.

Fear of and fascination with venomous snakes has influenced human perceptions of religion, spirituality, supernaturalism, and medicine. One of the most common hazards spanning the dynasties of ancient Egypt was injury by snakes or scorpions. The Brooklyn Papyrus, written during the 30th dynasty (380e343 BCE), constitutes what may be considered one of the earliest known treatises dedicated to the treatment of snakebites. Treatments consisted of emetics, incantations, and spells, with a focus on relieving the victim of spiritual and physical “poison.” Unlike the relatively brief comments regarding the treatment of snakebites in the earlier Smith Surgical Papyrus of the 18th dynasty (circa 1550 BCE), the Brooklyn Papyrus included a section on the identification of medically important venomous snakes intended as a guide to direct treatment. Likewise, in his treatise De venenatis animalibus eorumque remediis (On venomous animals and their remedies), the physicianzoologist Philumenus of Alexandria (circa 180 CE) included discussion about a variety of venomous snakes and the corresponding symptoms and treatment of their bites; this translated work would later play an important role in Arabic medical lore on snakebite (Walker-Meikle, 2014). In contrast with many of the contemporary beliefs, some traditions did not automatically associate contact with a snake as causing inevitable non-propitious events or physically/spiritually damaging effects. In Indian antiquity (circa 100e300 CE), Ayurvedic and Tantric disciplines distinguished between snakebites that resulted in envenoming (savis _ a) and those that did not (nirvis _ a); they also recognized the progressive nature of serious envenoming and assigned greater difficulty to treating the effects of snakebites that reached deeper tissues after passage from the skin to the blood (Slouber, 2016). During the early Renaissance, the enigmatic alchemist/botanist/astrologer/medical practitioner, Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim1 (1493e1541; popularly known by his mercifully contracted Roman appellation, Paracelsus) contemplated the use of venoms during his search for the Azoth, the spiritual medicine of humankind. The common thread between the earliest clinical perceptions of envenomation and latter views during the Middle Ages was the prevailing belief that snakebites poisoned both the spiritual and physical being. The toxic effects of viper bites were believed to be due to “enraged spirits.” The first systematic investigation of snake venoms was performed by the seventeenth-century Italian physicianFranciscoRedi (1626e1698).Redi’s experiments revealed the toxic nature of snake venoms, established a relationship among dose, body weight, and toxicity, and demonstrated the enhanced lethal effect of venom introduced near a blood vessel. Interest in the pathophysiology and improved management of snakebites focused attention on the further characterization of venoms, but it was not until 1938 that Karl Slotta (1895e1987) and Heinz Fraenkel-Conrat (1910e1999) succeeded in isolating a toxin, crotoxin, fromthe venomof the medically important tropical rattlesnake or cascabel (Crotalus durissus terrificus). Improvements in protein biochemical separation and characterization methods rapidly advanced the knowledge of venoms and often provided a pharmacological basis for the clinical effects observed in victims of medically significant snakebites. An understandably disproportionate emphasis on biomedically relevant venom properties narrowed the focus of venom research, for the most part excluding snakes with oral secretions of unknown or little-known medical importance. The very limited funding afforded to snake venom research further restricted the scope of investigation. Snakes that possess enlarged posterior maxillary teeth (“rear fangs”) and rarely cause human mortality or morbidity were largely ignored. However, although this limited interest in the “mild venom” or “toxic saliva” of “rear-fanged” snakes resulted in sparse research of their oral secretions, these snakes did make their importance known. In the late 19th to early 20th centuries, several inquisitive herpetologists and physicians began to question whether some snakes perceived as “harmless,” such as hognose snakes (Heterodon spp.) and South American racers (Philodryas spp.), were “mildly venomous.” South African investigators began to report life-threatening cases of boomslang (Dispholidus typus) envenomation, and South American researchers conducted studies of Philodryas venom, noting that the reported effects of their bites sometimes resembled that of pit vipers.

این کتاب را میتوانید بصورت رایگان از لینک زیر دانلود نمایید.

نظرات کاربران