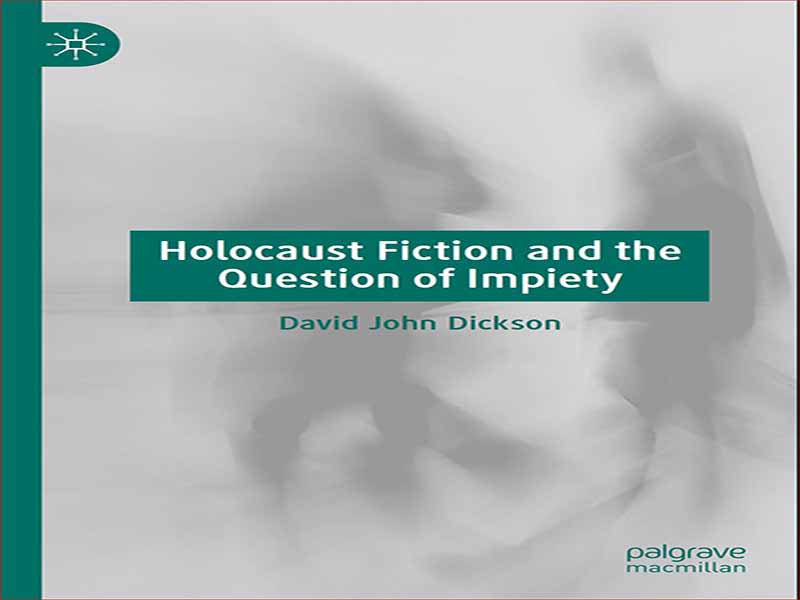

در گفتمان معاصر، اصطلاح بیتفاوتی هولوکاست – که توسط متیو باسبول ابداع شد، اگرچه از بحث گیلیان رز در مورد مفهوم تقوای هولوکاست در اثر اصلیاش سوگواری قانون میشود: فلسفه و بازنمایی مشتق شده است – مجموعهای از مفاهیم معانی خاصی را ایجاد کرده است. در متن رز، مفهوم بی تقوا به طور گسترده به نزدیکی روانی با عاملان و قربانیان هولوکاست مربوط می شود. او استدلال میکند که متون پرهیزگار موضعی از «غیرقابل بیان» و «نابازنمایی» اتخاذ میکنند (رز، 1996، ص 43)، زیرا قربانیان رویداد را بهدرستی انسانی و زمینهای نمیسازند، و نمیخواهند ارائه کنند. بینش روانشناسی که مرتکب این جنایات می شود. در عوض، متون پرهیزگار تمایل دارند دودویی ساده اخلاقی را انتخاب کنند. همانطور که بوسول می گوید: “تقوای هولوکاست فقط به وضوح دادگاه می پذیرد: به گناه و بی گناهی، به جرم و مجازات” (Boswell, 2012, p. 158). برای روشن کردن این موضوع، رز از مثال فهرست شیندلر (1993) اثر استیون اسپیلبرگ استفاده میکند، که او آن را نمونهای کهن الگوی تقوای هولوکاست میداند. فیلم اسپیلبرگ پرتره های عمیق و پیچیده ای از دو شخصیت اصلی خود، اسکار شیندلر و آمون گوث ارائه نمی دهد، بلکه دو تجسم انتزاعی از خیر و شر را ارائه می دهد. این فیلم به جای ایجاد حس تداوم بین «ابتذال خیرخواهی شیندلر و گرانی خشونت گوت» و پیشنهاد اینکه این دو مرد، با توجه به خاستگاه مشابه خود به عنوان اتریشی از «خانوادههای نامشخص»، ممکن است به راحتی موضع خود را تغییر دهند. درعوض، شیندلر را به عنوان یک «دمی خدا» (رز، 1996، ص 46؛ ص 47) و گوت را به عنوان یک دیوانه غیرقابل دسترس نشان می دهد. همانطور که رز بیان می کند، هدف متون پرهیزگار این است که “چیزی را که ما جرات درک آن را نداریم، رازآلود کنند، زیرا می ترسیم که ممکن است بسیار قابل درک باشد، بسیار پیوسته با آنچه ما هستیم – انسان، بسیار انسان” (رز، 1996). ، ص 43). بنابراین، به طور خلاصه، اصل اصلی درک رز از بی تقوایی هولوکاست این تصور است که هولوکاست را نباید به عنوان یک رویداد غیرقابل لمس و غیرقابل درک منحصر به فرد خارج از قلمرو درک انسانی دید. در عوض، متون غیرقانونی باید روانشناسی قربانیان و عاملان هولوکاست را قابل درک کند. رز بهخصوص رمان «بازماندههای روز» کازوئو ایشیگورو را ستایش میکند، بهعنوان مثال، بهخاطر تواناییاش در نشان دادن نفوذ خزنده ایدئولوژی فاشیستی به شیوهای که بهویژه با خواننده طنینانداز میشود. این کتاب با نشان دادن فساد آهسته پیشخدمت استیونز، در حالی که ارزشهای او به آرامی تغییر میکند و درک او از حیثیت به سمت «خدمت بیدریغ» به اربابش تغییر مییابد، کتاب «بحران هویت» را ترویج میکند (ص 52؛ ص 46). خواننده. منظور رز این است که خواننده مجبور می شود با استعداد بالقوه خود در برابر اشکال خاصی از نفوذ سیاسی روبرو شود، که نه تنها احساس امروزی ما را از درگیری با هولوکاست افزایش می دهد – زیرا مجبوریم از خود بپرسیم که چگونه می توانیم در زمینههای سیاسی معینی عمل کردهاند – اما همچنین بار دیگر تاکید میکند که هولوکاست نباید بهعنوان یک رویداد غیرقابل دسترسی منحصربهفرد در نظر گرفته شود. ما نباید هولوکاست را به عنوان چیزی غیرقابل درک مقدس بدانیم، همانطور که چهره هایی مانند الی ویزل و کلود لنزمن در گذشته چنین کرده اند – در واقع، لنزمن قبلاً اظهار داشته است که “فحاشی مطلق در پروژه درک وجود دارد” (Lanzmann, 2007, p. 51) – در عوض، ما باید با احساسات بیعمق اکثریت داستانهای اصلی هولوکاست با آثاری مقابله کنیم که به وضوح قربانیان و عاملان هولوکاست را زنده میکنند.

In contemporary discourse, the term Holocaust Impiety—coined by Matthew Boswell, though derived from Gillian Rose’s discussion of the concept of Holocaust Piety in her seminal work Mourning Becomes the Law: Philosophy and Representation—has come to develop a specific set of connotations. In Rose’s text, the concept of impiety relates broadly to a psychological proximity to the perpetrators and victims of the Holocaust. Pious texts, she argues, adopt a position of “ineffability” and “non-representability” (Rose, 1996, p. 43), as they do not properly humanise and contextualise the victims of the event, and nor do they wish to provide insight into the psychology that drives those perpetrating the atrocities. Instead, pious texts tend to opt for simple moral binaries. As Boswell puts it: “Holocaust piety admits only to the clarities of the courthouse: to guilt and innocence, to crime and punishment” (Boswell, 2012, p. 158). To elucidate this, Rose uses the example of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993), which she views as the archetypal example of Holocaust piety. Spielberg’s film does not provide depthful and complex portraits of its two principal characters, Oscar Schindler and Amon Goeth, but rather provides two abstract embodiments of good and evil. Rather than creating a sense of continuity between “the banality of Schindler’s benevolence and the gratuity of Goeth’s violence” and suggesting that these two men, given their similar origins as Austrians from “undistinguished families”, may easily reverse their positions, the film instead opts to represent Schindler as a “demi-God” (Rose, 1996, p. 46; p. 47) and Goeth as an unapproachably insane lunatic. Pious texts, as Rose puts it, aim to “mystify something that we dare not understand, because we fear that it may be all too understandable, all too continuous with what we are—human, all too human” (Rose, 1996, p. 43). In short, therefore, the core tenet of Rose’s understanding of Holocaust impiety is the notion that the Holocaust must not be viewed as an untouchably, incomprehensibly singular event outside of the realm of human understanding. Instead, impious texts must make the psychology of the victims and perpetrators of the Holocaust understandable. Rose particularly praises Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Remains of the Day, for instance, for its capacity to illustrate the creeping influence of fascist ideology in a way that resonates particularly with the reader. By illustrating the butler Stevens’s slow corruption, as his values slowly shift and his understanding of dignity is reframed towards “unstinting service” to his master, the book promotes a “crisis of identity” (p. 52; p. 46) in the reader. By this, Rose means that the reader is forced to confront their own potential susceptibility to certain forms of political influence, which not only heightens our present-day sense of engagement with the Holocaust—as we are forced to ask ourselves how we might have fared in certain political contexts—but also once again reasserts that the Holocaust is not to be regarded as an unreachably singular event. We must not regard the Holocaust as something incomprehensibly sacred, as figures such as Elie Wiesel and Claude Lanzmann have in the past—indeed, Lanzmann has previously asserted that there is an “absolute obscenity in the project of understanding” (Lanzmann, 2007, p. 51)—instead, we must counter the depthless sentimentality of the vast majority of mainstream Holocaust fiction with works that vividly bring to life the victims and perpetrators of the Holocaust.

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

نظرات کاربران