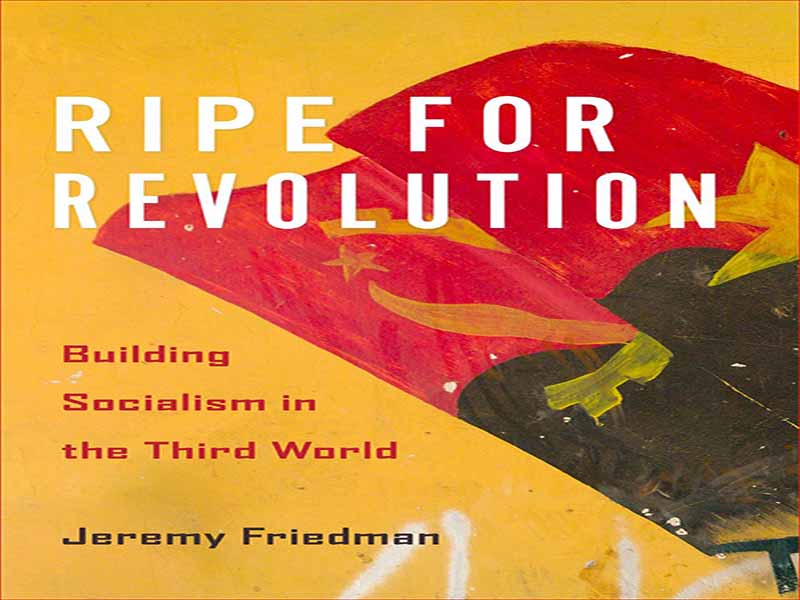

- عنوان کتاب: RIPE FOR REVOLUTION – Building Socialism in the Third World

- نویسنده/انتشارات: JEREMY FRIEDMAN

- حوزه: سوسیالیسم

- سال انتشار: 2022

- تعداد صفحه: 369

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 6.06 مگابایت

در 3 فوریه 1964، نخستوزیر چین، ژو انلای، در پایان یک تور پیشگامانه از ده کشور تازه استقلال یافته آفریقایی، در مقابل جمعیت زیادی در موگادیشو، سومالی، اعلام کرد: «چشمانداز انقلاب در سراسر قاره آفریقا عالی است». شانزده ماه بعد، قبل از بیست هزار نفر در استادیوم ملی در دارالسلام، تانزانیا، ژو اعلام کرد: «وضعیت بسیار مطلوب برای انقلاب امروز نه تنها در آفریقا، بلکه در آسیا و آمریکای لاتین نیز حاکم است». اظهارات ژو، که توسط برخی از مطبوعات غربی در بیانیهای مبنی بر اینکه آفریقا، آسیا و آمریکای لاتین «آماده انقلاب هستند» فشرده شد، موجی از شوک در سراسر جهان ایجاد کرد: جنگجویان سرد فداکار میترسیدند که چین سرخ در حال تلاش برای براندازی دولتهای جدید شکننده است. جهان در حال توسعه. 1 خشم به حدی رسید که رئیس جمهور خشمگین تانزانیا، جولیوس نیره، به سناتور رابرت کندی که می آمد گفت: “آفریقا برای انقلاب بسیار آماده است و می توانم به شما اطمینان دهم که چو ان لای مسئول نیست.” بدون شک درست است که انرژی های انقلابی نیازی به کاشت مصنوعی توسط بیگانگان شرور نداشت. با فروپاشی نظام امپریالیستی، دولتهای نوپای پسااستعماری در مواجهه با فقر ناامیدکننده و بیثباتی سیاسی در سرتاسر جهان سوم، با امیدهای هزار ساله برای رفاه مواجه شدند.3 تحول انقلابی در دستور کار بسیاری در آفریقا، آسیا و آمریکای لاتین بود، اما چه نوع انقلاب؟ هیچ پرولتاریایی برای تصاحب وسایل تولید وجود نداشت، و ابزار تولید زیادی برای تصاحب وجود نداشت. مدلهای مارکسیستی انقلاب، چه در انواع مائوئیستی، استالینیستی، تیتوئیستی، یا انواع دیگر، در زمینههای سیاسی و اقتصادی بسیار متفاوت شکل گرفته بودند – و با خونهای بسیار ریخته شده. توسعه از طریق سرمایه داری به عنوان یک کار دشوار و طولانی تلقی می شد – ناگفته نماند که یکی از نیروهای محرک امپریالیسم بود که بر این مناطق سرکوب کرده بود. سوسیالیسم یکی دیگر از راه های پیش رو بود. اما چگونه می توان آن را با شرایط جهان سوم تطبیق داد؟ به تعداد کشورها و رهبرانی که مایل بودند نسخهای از سوسیالیسم را امتحان کنند، پاسخها وجود داشت. در دهه های اول پس از جنگ جهانی دوم، زمانی که کشورهای آسیایی و سپس آفریقایی استقلال خود را به دست آوردند، هیچ کس – چه در پکن، قاهره، جاکارتا، مسکو، دهلی نو یا جاهای دیگر- دقیقاً نمی دانست که چگونه سوسیالیسم را در کشورهای تازه استقلال یافته بسازد. پیشینه هایی وجود داشت: نه چین و نه روسیه در زمان انقلاب های خود کشورهای بسیار صنعتی نبودند، و شوروی ها به ویژه تجربه جمهوری های آسیای مرکزی خود را مرتبط با جهان پسااستعماری می دانستند. انقلاب سوسیالیستی را در پیشرفتهترین اقتصادهای سرمایهداری تصور میکردند، مارکسیسم-لنینیسم در عوض به روشی برای «رسیدن» به آنها تبدیل شد. (5) اما چین و روسیه نیز کشورهای عظیمی با بازارهای داخلی بزرگ و منابع طبیعی عظیم بودند، حداقل برخی از آنها. صنعت، و شاید مهمترین، رژیمهای کمونیستی قدرتمندی که خود را از نظر نظامی در بحران جنگ داخلی تثبیت کرده بودند. بیشتر کشورهای آفریقایی و آسیایی عمدتاً کشورهای دهقانی با صنعت اندک و طبقات کارگر کوچک بودند، که در آنها کمتر اجتماعی کردن وسایل تولید مطرح بود تا ایجاد آنها. اما نظامهای سیاسی – و در برخی موارد، یک هویت ملی منسجم – نیز باید ساخته میشد. همه اینها باید در جوامعی اتفاق میافتد که شکافهای قومی در آنها وجود داشت و در آنها مبارزه آزادیبخش اغلب بر هویتهایی غیر از طبقات متمرکز بود، و نهادهای مذهبی فراگیر و از نظر سیاسی تأثیرگذار بودند. بعلاوه، در حالی که برخی از رهبران کشورهای تازه استقلال یافته با مارکسیسم همدل بودند، اکثر آنها اینگونه نبودند، و تعداد بسیار کمی از آنها مشتاق بودند که از الگوهای چینی یا شوروی تقلید کنند یا اجازه دهند قدرت خارجی دیگری به حاکمیت آنها که به سختی به دست آمده است، تجاوز کند.

On February 3, 1964, standing in front of a large crowd in Mogadishu, Somalia, at the end of a groundbreaking tour of ten newly independent African states, Chinese premier Zhou Enlai declared, “Revolutionary prospects are excellent throughout the African continent.” Sixteen months later, before twenty thousand at the National Stadium in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, Zhou proclaimed, “An exceedingly favorable situation for revolution prevails today not only in Africa, but also in Asia and Latin America.” Zhou’s remarks, condensed by some in the Western press into a declaration that Africa, Asia, and Latin America were “ripe for revolution,” sent shockwaves around the world: dedicated Cold Warriors feared that Red China was attempting to subvert the fragile new states of the developing world.1 The furor reached such a high pitch that Tanzania’s exasperated president, Julius Nyerere, told visiting senator Robert Kennedy that “Africa is very much ripe for revolution and I can assure you Chou En Lai is not responsible.”2 Nyerere was undoubtedly right that revolutionary energies did not need to be artificially implanted by nefarious outsiders. As the imperialist system crumbled, fledgling postcolonial governments faced millennial hopes for prosperity in the face of desperate poverty and political instability throughout the Third World.3 Revolutionary transformation was on the agenda of many in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, but what sort of revolution? There was no proletariat to seize the means of production, and not much means of production to seize. Marxist models of revolution, whether in Maoist, Stalinist, Titoist, or other variants, had taken form in very different political and economic contexts—and with much blood spilled. Development through capitalism was seen as a long, difficult slog—not to mention that it was one of the driving forces of the imperialism that had oppressed these regions. Socialism was another possible way forward. But how could it be adapted to Third World conditions? There were as many answers as there were countries and leaders willing to try some version of socialism. In the first decades after World War II, as Asian and then African countries gained their independence, no one—whether in Beijing, Cairo, Jakarta, Moscow, New Delhi, or elsewhere—knew exactly how to build socialism in the newly independent states. There were precedents: neither China nor Russia had been highly industrialized countries at the time of their revolutions, and the Soviets in particular saw the experience of their Central Asian republics as relevant to the postcolonial world.4 As Fred Halliday has pointed out, while Marxism had envisioned socialist revolution as taking place in the most advanced capitalist economies, Marxism-Leninism became instead a method for “catching up” with them.5 But China and Russia were also enormous countries with large internal markets and vast natural resources, at least some industry, and, perhaps most important, powerful communist regimes that had established themselves militarily in the crucible of civil war. Most African and Asian states were predominantly peasant countries with little industry and tiny working classes, where it was less a matter of socializing the means of production than creating them. But political systems—and, in some cases, a coherent national identity—also needed to be constructed. All of this had to happen in societies riven by ethnic divisions in which the liberation struggle had often been centered on identities other than class, and where religious institutions were pervasive and politically influential. Additionally, while some of the leaders of the newly independent states were sympathetic to Marxism, most were not, and very few were anxious either to copy the Chinese or Soviet models or to allow another outside power to infringe upon their hard-won sovereignty.

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

Download: RIPE FOR REVOLUTION – Building Socialism in the Third World

نظرات کاربران