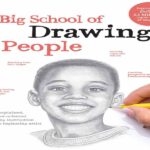

- عنوان کتاب: Post-Traumatic Growth to Psychological Well-Being

- نویسنده: Melanie Munroe

- حوزه: کسالت

- تعداد صفحه: 309

- سال انتشار: 2022

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 7.07 مگابایت

درک مقدمات و رشد خرد برای من یک علاقه مادام العمر بوده است. به عنوان یک دوره کارشناسی، من این شانس را داشتم که در دانشگاه کلارک شرکت کنم، که در آن زمان یکی از معدود برنامه های روانشناسی بود که رفتارگرایانه نبود اما در عوض بر نظریه های آلمانی توسعه در طول عمر تأکید داشت (به عنوان مثال، ورنر، 1957). من بسیار تحت تأثیر کتابی از رابرت گریوز (1960) به نام تماشای طلوع باد شمالی بودم که در آن او استدلال می کرد که سختی برای پیشرفت مثبت هم برای مردم و هم برای جوامع کاملاً ضروری است. آنچه من واقعاً می خواستم انجام دهم این بود که بفهمم چرا و چگونه بزرگسالان استثنایی استثنایی می شوند، و من گمان می کردم که ناملایمات با آن ارتباط دارد – قطعاً یک فکر اصلی نیست، بلکه بیشتر در حوزه دین و فلسفه رخ می دهد تا در روانشناسی. همانطور که تعدادی از نویسندگان جلد فعلی اشاره کرده اند.

در اولین سال تحصیلات تکمیلی خود در زمینه رشد بزرگسالان در دانشگاه کالیفرنیا سانفرانسیسکو (بیش از 40 سال پیش!)، من هر آنچه را که می توانستم در مورد رشد استثنایی توسط نویسندگانی مانند Vaillant، Levinson، White، Jung، Gough و البته روانی اریکسون خواندم. ¬زندگینامه گاندی و لوتر. همه این نویسندگان رشد استثنایی بزرگسالان را توصیف کردند، اما بسته به مفروضات رشته تحصیلی خود از اصطلاحات مختلفی استفاده کردند. هیچ کدام راهی برای تعریف و اندازه گیری توسعه استثنایی ارائه نکردند. من برای مارجوری فیسک لوونتال، که به تعهد نگاه می کرد، برخی از تاریخچه های زندگی را کدنویسی کردم، و به ذهنم رسید که افرادی که فکر می کردم استثنایی (یعنی عاقل ترین) در نمونه بودند، اغلب بسیار متواضع بودند و احتمالاً خودشان را اینگونه توصیف نمی کردند. عاقل بنابراین من در مورد چگونگی اندازه گیری خرد غافل بودم، اما به سخنرانی قدیمی برنیس نوگارتن و بیل هنری برخوردم که می گفت، اگر می خواهید بدانید شخصیت یک شخص واقعاً چگونه است، تحت استرس به آن نگاه کنید. آه، من فکر کردم، شاید خرد نتیجه ای از نحوه کنار آمدن افراد با استرس باشد! بنابراین من به مطالعه مقابله با ریچارد لازاروس رفتم و متوجه شدم که ما نیز در مورد چگونگی اندازه گیری مقابله نمی دانیم، بنابراین در نهایت روی آن تمرکز کردم.

به عنوان یک محقق فوق دکترا در UC Irvine، من با Dan Stokols برای ایجاد یک مدل نظری جدید در مورد استرس کار کردم. ادبیات در مورد اثرات نامطلوب طولانی مدت استرس دوران کودکی شروع به ظهور کرده بود، اما نه دن و نه من، که هر دو والدین خود را در کودکی از دست داده بودیم، فکر نمیکردیم که این تمام ماجرا بود – که استرس دوران کودکی لزوماً منجر به زندگی مادامالعمر نمیشود. فاجعه، و چیزهای مثبت نیز می تواند از تجربه استرس ناشی شود. ما همه چیزهایی را که میتوانستیم پیدا کنیم که پیامدهای مثبت استرس را ذکر میکردند (که عمدتاً توسط روانپزشکان بهعنوان انکار نادیده گرفته شد) را بررسی کردیم و یک مدل تقویت انحراف استرس ایجاد کردیم – که استرس بسته به ویژگیهای زمینهای و شخصی میتواند منجر به پیامدهای مثبت یا منفی شود. خصوصیات (آلدوین و استوکولز، 1988).

با توجه به اینکه همه ما در آن زمان چقدر سخت کار میکردیم تا جامعه زیست پزشکی را متقاعد کنیم که استرس روانی-اجتماعی اثرات نامطلوبی بر سلامتی دارد، به عقب برگردیم و بگوییم که میتواند اثرات مثبتی داشته باشد، حداقل بحثبرانگیز بود و ما قبل از آن. کار مقدماتی بر روی پیامدهای مثبت قرار گرفتن در معرض جنگ، مشاجرات زیادی را برانگیخت (آلدوین و همکاران، 1994). خوشبختانه، محققان دیگری مانند افلک و همکاران نیز شروع به کار روی این موضوع کردند. (1987)، کالهون و تدسکی (1990)، فولکمن و مسکوویتز (2000)، و یالوم و لیبرمن (1981).

در آن زمان، مطالعه چنین موضوعاتی مانند حکمت حتی بدعت آمیزتر بود. بنابراین، بسیار سپاسگزار بودم که افراد برجسته در این زمینه، مانند کلیتون و بیرن (1980)، هالیدی و چندلر (1986)، استرنبرگ (1990)، الکساندر و لانگر (1990)، و بالتز و استودینگر (1993) ، توانستند از قامت خود برای معرفی مطالعه علمی این موضوع فوق العاده مهم استفاده کنند.

در این زمان، شوهرم، مایکل (“ریک”) لونسون در حال کار بر روی مدلی از رشد استثنایی بزرگسالان بود که او آن را مدل “رهایی” نامید (Levenson & Crumpler, 1996; Levenson et al., 2001). یک دانشجوی فارغ التحصیل ما، تیش جنینگز، اشاره کرد که کار من در مورد رشد مرتبط با استرس (SRG) و ریک در مورد توسعه استثنایی می تواند (و باید) در یک نظریه خرد ترکیب شود. بنابراین، ما یک قطعه در مورد استرس به عنوان زمینه ای برای رشد در بزرگسالی نوشتیم (آلدوین و لونسون، 2004). این امر در تاخت و تاز ما به مدل خود تعالی خرد بسط داده شد (لوونسون و همکاران، 2005؛ آلدوین و همکاران، 2019). پایان نامه تیش که مدل ما را آزمایش کرد نشان داد که قرار گرفتن در معرض مبارزه به خودی خود منجر به خردمندی در زندگی بعدی نمی شود، بلکه نحوه ارزیابی و مقابله با آن بود (جنیگز و همکاران، 2006).

بنابراین، من کاملاً خوشحال شدم که متوجه شدم ملانی مونرو و میشل فراری کتابی را با عنوان رشد پس از سانحه تا بهزیستی روانی: مقابله عاقلانه با ناملایمات تهیه میکنند.

Understanding the antecedents and development of wisdom has been a lifelong pas¬sion for me. As an undergraduate, I had the good fortune to attend Clark University, which was one of the few programs in psychology at the time that was not behav¬ioristic but instead emphasized German theories of development across the lifespan (e.g., Werner, 1957). I was very much influenced by a book by Robert Graves (1960), called Watch the North Wind Rise, in which he argued that adversity was absolutely necessary for positive development for both people and societies. What I really wanted to do was to understand why and how exceptional adults became exceptional, and I suspected that adversity had something to do with it – certainly not an original thought, but one that occurred more in the domain of religion and philosophy than in psychology, as several of the authors in the current volume have noted.

In my first year graduate school in adult development at UC San Francisco (over 40 years ago!), I read everything I could about exceptional development by authors such as Vaillant, Levinson, White, Jung, Gough, and, of course, Erikson’s psycho¬biographies of Gandhi and Luther. All of these authors described exceptional adult development, but used different terms, depending upon the assumptions of their academic discipline. None provided a way of defining and measuring exceptional development. I did some coding of life histories for Marjorie Fisk Lowenthal, who was looking at commitment, and it occurred to me that the individuals I thought were exceptional (i.e., wisest) in the sample were often very modest and probably wouldn’t describe themselves as wise. So I was at a loss as to how to measure wis¬dom, but came across an old talk by Bernice Neugarten and Bill Henry that said that, if you want to know what a person’s personality was really like, look at it under stress. Aha, I thought, perhaps wisdom is an outcome of how individuals cope with stress! So I went to study coping with Richard Lazarus, and discovered that we didn’t know much about how to measure coping, either, so I ended up focusing on that.

As a postdoctoral scholar at UC Irvine, I worked with Dan Stokols to develop a new theoretical model on stress. Literature was starting to emerge on the long-term adverse effects of childhood stress, but neither Dan nor I, who had both lost a parent as children, thought that was the whole story – that childhood stress did not neces¬sarily result in a lifelong calamity, and that positive things could also arise from experiencing stress. We reviewed everything we could find that mentioned positive outcomes of stress (which were largely dismissed by psychiatrists as denial), and developed a deviation amplification model of stress – that stress could result in either positive or negative outcomes, depending on contextual and personal charac¬teristics (Aldwin & Stokols, 1988).

Given how hard we all had to work at the time to convince the biomedical com¬munity that psychosocial stress had adverse health effects, to turn around and say that it could have positive effects was, to say the least, controversial, and our pre¬liminary work on the positive outcomes of combat exposure provoked a great deal of contention (Aldwin et al., 1994). Luckily, other researchers were also starting to work on this, such as Affleck et al. (1987), Calhoun and Tedeschi (1990), Folkman and Moskowitz (2000), and Yalom and Lieberman (1981).

At that time, it was even more heretical to study such “squishy” subjects as wis¬dom. Thus, I was very grateful that luminaries in the field, such as Clayton and Birren (1980), Holiday and Chandler (1986), Sternberg (1990), Alexander and Langer (1990), and Baltes and Staudinger (1993), among others, were able to use their stature to introduce the scientific study of this extremely important topic.

About this time, my husband, Michael (“Rick”) Levenson was working on a model of exceptional adult development he called the “liberative” model (Levenson & Crumpler, 1996; Levenson et al., 2001). A graduate student of ours, Tish Jennings, pointed out that my work on stress-related growth (SRG) and Rick’s on exceptional development could (and should) be combined into a theory of wisdom. Thus, we wrote a piece on stress as a context for development in adulthood (Aldwin & Levenson, 2004). This was extended into our foray into the self-transcendence model of wisdom (Levenson et al., 2005; Aldwin et al., 2019). Tish’s dissertation testing our model showed that it wasn’t exposure to combat per se that led to wis¬dom in later life, but rather how one appraised and coped with it (Jennings et al., 2006).

Thus, I was absolutely delighted to learn that Melanie Munroe and Michel Ferrari were putting together a book, entitled Post-traumatic Growth to Psychological Well-Being: Coping Wisely with Adversity.

این کتاب را میتوانید بصورت رایگان از لینک زیر دانلود نمایید.

نظرات کاربران