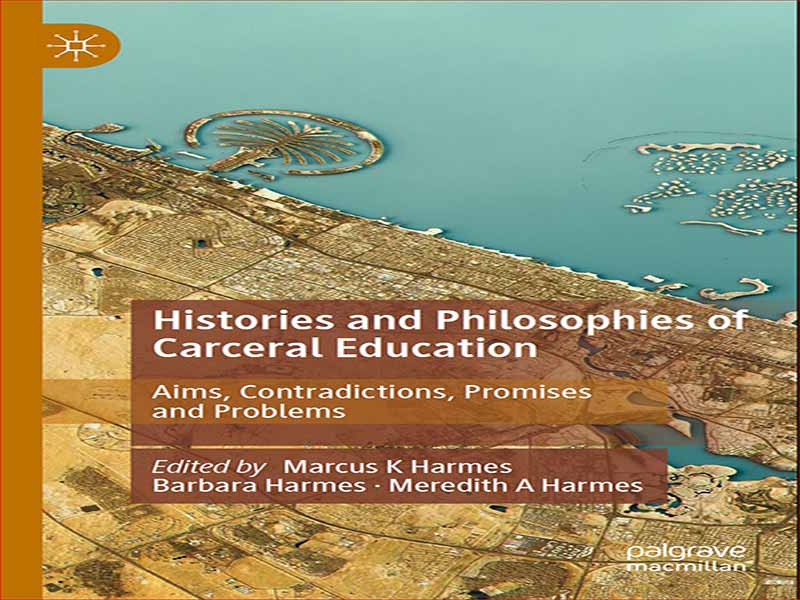

- عنوان کتاب: Histories and Philosophies of Carceral Education

- نویسنده/انتشارات: Marcus K Harmes

- حوزه: زندان

- سال انتشار: 2022

- تعداد صفحه: 282

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 5.27 مگابایت

جمعیت جهانی زندانیان همچنان در حال رشد است و تنها بخش نسبتاً کمی از زندانیان جهان به آموزش رسمی دسترسی دارند یا آن را انجام می دهند (Gottschalk, 2006, pp. 1, 181; Kilgore, 2015, p. 18). ارائه آموزش در زندان ها نه تنها چالش های لجستیکی و فنی را به همراه دارد، بلکه یک موضوع حساس و فرهنگی برای دولت ها و جوامع است. دولتهایی که به دنبال ارائه یک دستور کار سیاسی «سخت در قبال جرم» یا «قانون و نظم» با سیاستهایی هستند که میزان حبس را افزایش میدهند، ممکن است متوجه شوند که اقدام همزمان یا مکمل رویکرد آنها دسترسی زندانیان به آموزش را قطع میکند. انگیزههای تنبیهی که دوران حبسهای جمعی را پیش میبرد، همچنین میتواند باعث محدودیت آموزش برای افراد در زندان شود و بیشتر باعث کاهش بودجه به برنامههای آموزشی شود (استرن، 2014). خرج کردن پول مالیات دهندگان برای آموزش زندان ها به خوبی به عنوان یک موضوع احساسی توصیف می شود (بهان، 2021). اشاره به ارتباط قابل تشخیص بین ضد تکرار جرم و آموزش (به عنوان مثال به اسپرین 2010؛ الیسون و همکاران، 2017؛ باتامز و همکاران، 2021 مراجعه کنید) ممکن است برای رفع نگرانی جامعه یا خنثی کردن گفتمان سیاسی در مورد انتقاد از استفاده از پول عمومی کافی نباشد. برای آموزش زندانیان برخی از اقدامات، مانند قطع بودجه Pell در اواسط دهه 1990، نمونههای به خوبی مستند کاهش منابع برای آموزش زندانیان، با نتیجه مرتبط با محدود کردن آموزش به جمعیت بزرگی از افراد از اقلیتها هستند (Lillis, 1994؛ اسلاتر، 1995). حتی در مواردی که سیاستهای مثبت یا عمدی برای دسترسی به آموزش وجود دارد، ممکن است شکافی بین سیاست و واقعیت در حال وقوع در داخل یک مرکز اصلاحی وجود داشته باشد (Behan, 2021؛ Czerniawski, 2016). نکته قابل توجه، در حالی که بسیاری از فعالیتهای آموزشی جریان اصلی دور از دید عموم مردم انجام میشود (والدین معمولاً در کلاسهای درس فرزندانشان نیستند)، آموزش زندان حتی برای جامعه گستردهتر بهطور جدیتر نامرئی است. این نامرئی بودن ممکن است دو مفهوم داشته باشد. درک یا دیدن ارزش چیزی که دور از چشم اتفاق می افتد برای جامعه وسیع تری دشوار است. به همین ترتیب، افرادی که در زندان هستند ممکن است بتوانند معنای خود را از تلاش آموزشی خود ایجاد کنند. رویکردهای آموزش زندان در واقعیتهای تاریخی مختلف و مفاهیم فلسفی در حال تغییر از حبس و آموزش در طول دههها و قرنها ریشه دارد. این تنوع در فصلهای این مجموعه منعکس شده است که در آن شیوههای آموزشی از نظر رویکرد و سطح، از تحصیلات عالی، هنر، مشاوره زندان، و مذهب گرفته تا آموزش مجدد مجرمان جنسی، تا نیات و حتی فلسفههای مختلف از جمله توانبخشی و توانمندسازی اعمال کیفری که اروپاییان را در قرن هجدهم به استرالیا و قاره آمریکا آورد، یکی از ابعاد این تاریخ است. یکی دیگر از ابعاد یک تاریخ پیچیده و بحث برانگیز، شیوه ای است که مقامات و مربیان به دنبال آموزش زندانیان بوده اند، یا برعکس، جایی که ممنوع یا محدود شده است.

The global prison population continues to grow, and only a relatively small proportion of the world’s incarcerated people have access to or undertake formal education (Gottschalk, 2006, pp. 1, 181; Kilgore, 2015, p. 18). Delivering education in prisons not only presents logistical and technical challenges, but is also a sensitive and culturally charged issue for governments and communities. Governments seeking to deliver a ‘tough on crime’ or ‘law and order’ political agenda with policies that drive up the rates of incarceration may also find that a concomitant or complementary action to their approach is cutting off prisoners’ access to education. The punitive impulses that drive the era of mass incarceration can also drive the restriction of education to people in prison and further drive the cutting of funds to education programs (Stern, 2014). Spending tax payer money on the education of prisons is well described as an emotional issue (Behan, 2021). Pointing to the discernible connections between anti-recidivism and education (see for example Esperian 2010; Ellison et al., 2017; Battams et al., 2021) may not be enough to dispel community concern or neutralise political discourse regarding criticism of using public money to educate prisoners. Certain measures, such as the cutting of the Pell Funding in the mid-1990s, are well documented instances of the reduction of resources for prisoner education, with the associated outcome of restricting education to a large population of peo¬ple from minorities (Lillis, 1994; Slater, 1995).

Even where there are positive or intentional policies in place to provide access to education, there may well be a gap between policy and the trans¬piring reality inside a correctional facility (Behan, 2021; Czerniawski, 2016). Notably, while much mainstream educational activity takes place out of sight of the general population (parents are not normally in their children’s classrooms), prison education is even more emphatically invis¬ible to the wider community. That invisibility may have a two-fold impli¬cation. It is hard for a wider community to sense or see the value in what is taking place out of sight. Equally, people who are incarcerated may be able to create their own meaning out of their educational endeavour.

Approaches to prison education are anchored in different historical realities and shifting philosophical conceptions of incarceration and edu¬cation over decades and centuries. This diversity is reflected in the chap¬ters in this collection where educational practice ranges in approach and level, from tertiary study, art, prison consultancy, and religion to the re-education of sex offenders, to different intentions and even philosophies including rehabilitation and empowerment. The penal practices that brought Europeans to Australia and the Americas in the eighteenth cen¬tury are one dimension of this history. Another dimension of a complex and contested history is the way that authorities and educators have sought to educate the incarcerated, or conversely where that has been prohibited or limited.

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

نظرات کاربران