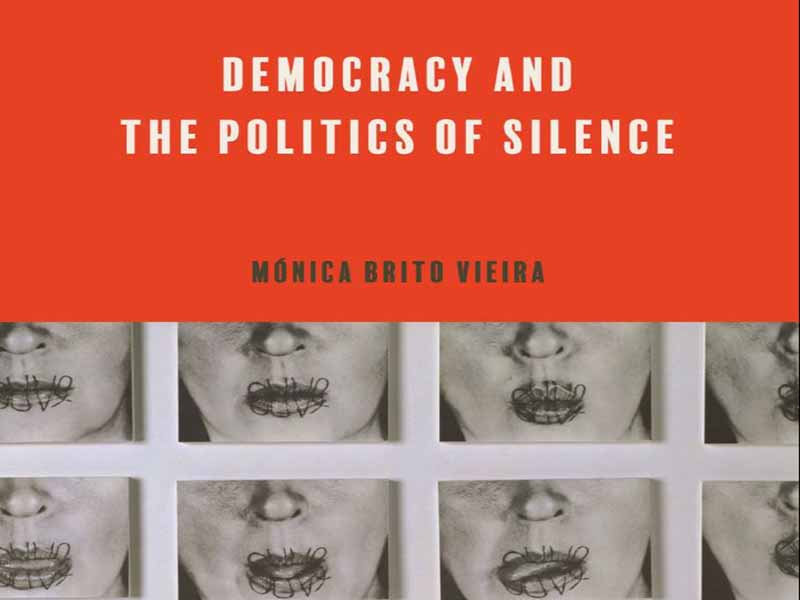

- عنوان کتاب: Democracy and the Politics of Silence

- نویسنده: Mónica Brito Vieira

- حوزه: رقابت کشورها

- سال انتشار: 2025

- تعداد صفحه: 237

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 0.8 مگابایت

این کتابی است درباره سکوت به عنوان بُعدی اساسی از زندگی دموکراتیک. هر چقدر هم که این جمله ساده به نظر برسد، در عین حال در تناقض پیچیدهای نیز هست. تطابق بنیادین بین سیاست و گفتار، یکی از – اگر نگوییم – محکمترین اصول سیاست است. هانا آرنت این نکته را به طرز تکاندهندهای بیان میکند: «هر جا که اهمیت گفتار مطرح باشد، مسائل بنا به تعریف سیاسی میشوند، زیرا گفتار همان چیزی است که انسان را به موجودی سیاسی تبدیل میکند» (1958، 9). سخنان آرنت پیشینهای طولانی دارد. ارسطو اولین کسی بود که انسانها را سیاسی دانست: آنها گفتار را در کنار خود داشتند و از گفتار برای فهمیدن چگونگی زندگی مشترک استفاده میکردند. برای ارسطو، گفتار زیربنای یک شکل متمایز انسانی از اجتماعی بودن است که مبتنی بر قضاوتهای منطقی و ارتباطی در مورد «سود و زیان و از این رو همچنین عادلانه و ناعادلانه» است (1996، 1253a8). با ارسطو، گفتار به چیزی بیش از یک ویژگی تعریفکننده گونه انسان تبدیل شد. این واژه مترادف با خود شهر شد، که اکنون به عنوان پیوندی در گفتار برای جستجوی خیر و عدالت درک میشود. دیدگاه ارسطویی در مورد گفتار به عنوان چیزی که وجود سیاسی را تشکیل میدهد و قدرت بخشیدن به آن را دارد، فقط یک ادعای توصیفی نیست. این یک ادعای ارزیابی در مورد چیستی سیاست و چیستی آن است. به این ترتیب، گفتار نمونهای از خود سیاست است که مسئول شکلدهی به نحوهی نگرش ما به سیاست و آنچه که میبینیم – و نمیبینیم – وقتی به آن نگاه میکنیم، میباشد. با ارتقاء گفتار به عقلِ مختص سیاست، آنچه در خارج از گفتار قرار دارد از سیاست تبعید شده است. آتنا آتاناسیو مینویسد: «بیانات خاموش یا صوتی که با معناشناسی انضباطی زبان مناسب مطابقت ندارند» «از واژگان سیاست حذف شدهاند» و «به پیشا-سیاسی یا ضد-سیاسی تنزل یافتهاند، یا بیربط یا خرابکارانه تلقی میشوند» (2017، 260). سکوت تا همین اواخر، زمانی که اصلاً در مطالعهی سیاست مطرح شده است، اینگونه بوده است: به عنوان یک امر بیرونی خطرناک یا یک وسیلهی یدکی ناچیز. سکوت که عملاً با منفیگرایی – شکست، غیاب، فقدان – مرتبط است، خود را به عنوان نوعی هیچچیز که به طور طبیعی و بدون مشکل ممکن است از حوزه ادراک سیاسی فرار کند، به حاشیه رانده شده است. مسیری که ما را به این نقطه میرساند، روشن است. در سیاست، امور سیاسی مطالعه میشوند. گفتار به عنوان چیز سیاست، نحوه انجام آن، نحوه مشارکت ما در آن، مطرح شده است. سکوت، نقطه مقابل آن است. عدم تقارن تثبیتشده بین گفتار و سکوت به عنوان چهره و زمینه سیاست، نه تنها با درک ما از آنچه سیاست محسوب میشود، بلکه با محدودیتهای روششناختی که مفهومسازی سکوت به عنوان هیچچیز را تعیین میکنند و از آن ناشی میشوند، توضیح داده میشود. زیرا چگونه میتوان یک هیچچیز، یک عدم وقوع، چیزی که غایب است را تشخیص داد، چه رسد به مطالعه؟ چگونه میتوان چیزی را مطالعه کرد که هیچ ردی از خود به جا نمیگذارد و هیچ مدرکی از آن وجود ندارد؟ پاسخ مرسوم این است که سکوت برای مطالعه نامناسب است (Zerubavel 2006, 13; Schröter 2013, 42). این به عنوان یک آستانه شناختی در نظر گرفته میشود و مانعی است که نمیتوان از آن عبور کرد. آنچه که من در مورد سیاست به طور کلی گفتهام، با قدرت ویژهای در مورد سیاست دموکراتیک نیز صدق میکند. دموکراسی بر پایه برابری در رابطه با بیان بنا شده است. این شامل برابری هر شهروند سخنگو با هر شهروند سخنگو دیگر و حق برابر آنها برای خطاب قرار دادن یکدیگر در مشورت عمومی است. با شهروندی شفاهی، هنجار، چه به معنای مطلوب بودن و چه به معنای “هنجار”، فرآیندهای شفاهی کنشگری و تصمیمگیری – هر چقدر هم که در تجربه روزمره شهروندان نادر باشند – آرمان دموکراسی را تعیین کردهاند (جی. گرین ۲۰۱۰، ۱۱). بر این اساس، نظریهپردازان دموکراتیک تمایز بین مشارکت سیاسی و عدم مشارکت سیاسی را به ترتیب به بیان و سکوت نسبت دادهاند (بری ۱۹۷۴، ۹۱). آنها حدس زدهاند که “اگر بیان عمل است، پس سکوت، عدم عمل است” (لانگتون ۱۹۹۳، ۳۱۴).

This is a book about silence as a fundamental dimension of democratic life. As simple as the statement may sound, it is also wrapped in paradox. The constitutive coincidence between politics and speech is one of the—if not the—most firmly established principles of politics. Hannah Arendt makes the point most poignantly: “Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being” (1958, 9). Arendt’s words have a long pedigree. Aristotle was the first to deem humans political: they had speech on their side and used speech to figure out how to live together. For Aristotle, speech underpins a distinctively human form of sociality based on reasoned and communicative judgments about “the advantageous and the harmful and hence also the just and the unjust” (1996, 1253a8). With Aristotle, speech developed into more than just a feature defining the human species. It became synonymous with the polis itself, now understood as an association in speech for the pursuit of the good and the just. The Aristotelian view of speech as that which constitutes and has the power to endow political existence with normative value is not just a descriptive claim. It is an evaluative claim about what politics is and what it is about. As such, it is an instance of politics itself, responsible for shaping how we have come to see politics and what it is that we see—and do not see—when we look at it. With speech elevated to the reason proper to politics, what lies outside speech has been exiled from politics. Athena Athanasiou writes, “Silent or vocal articulations that do not conform to the disciplinary semantics of proper language” have been “excluded from the lexicon of politics” and “relegated to the pre-political or anti-political, [deemed] either irrelevant or subversive” (2017, 260). This is how silence has figured until recently, when it has figured at all, in the study of politics: as a dangerous outside or a negligible spare. Practically associated with negativity—failure, absence, lack—silence has found itself marginalized as the kind of no-thing that naturally and unproblematically might escape the field of political perception. The route taking us to this point is clear. In politics, one studies political things. Speech has been cast as the thing of politics, the way it is done, the way we partake in it. Silence, its opposite. The established asymmetry between speech and silence as the figure and ground of politics is explained not just by our understanding of what counts as politics but also by methodological limitations that determine, and ensue from, the conceptualization of silence as no-thing. For how might one recognize, let alone study, a no-thing, a non-occurrence, something that is absent? How might one study that which leaves no trail, of which there is no evidence? The conventional answer is that silence is unfit for study (Zerubavel 2006, 13; Schröter 2013, 42). Figured as a cognitive threshold, it is a barrier that cannot be crossed. What I have said about politics in general applies with special force to democratic politics. Democracy is founded on equality with regard to speech. This comprises the equality of every speaking citizen with every other speaking citizen and their equal right to address each other in public deliberation. With vocal citizenship the norm, both in the sense of being considered desirable and “the norm,” vocal processes of activism and decision-making— however rare they might be in citizens’ everyday experience— have set the ideal of democracy (J. Green 2010, 11). Accordingly, democratic theorists have mapped out the distinction between political participation and political nonparticipation to speech and silence, respectively (Barry 1974, 91). “If speech is action,” they have surmised, “then silence is failure to act” (Langton 1993, 314).

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

Download: Democracy and the Politics of Silence

نظرات کاربران