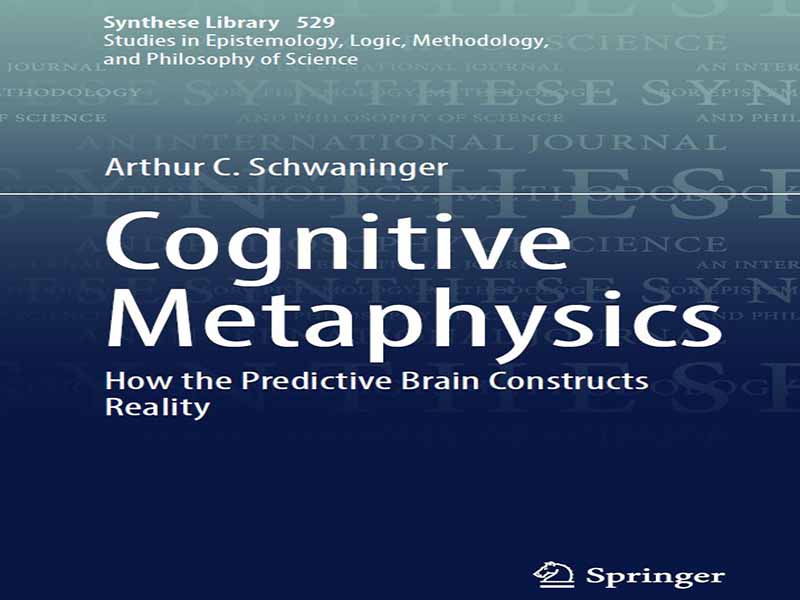

- عنوان کتاب: Cognitive Metaphysics

- نویسنده: Arthur C. Schwaninger

- حوزه: متافیزیک

- سال انتشار: 2025

- تعداد صفحه: 257

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 5.92 مگابایت

وقتی معمولاً با جهان روبرو میشویم، متوجه میشویم که آن از پیش به اشیاء مختلفی از انواع مختلف و از پیش تعیینشده تقسیم شده است. برای مثال، ما جهان را متشکل از موجودات زنده و غیرزنده میبینیم. با نگاهی دقیقتر به قلمرو موجودات زنده، متوجه میشویم که برخی از موجودات زنده از جهات خاصی، مانند ظاهر، رفتار یا کد ژنتیکی، بیشتر شبیه یکدیگر هستند تا سایر موجودات زنده. ما به طور غریزی این موجودات را با معرفی دستههای خاصی در زبان خود، مانند «سگ»، گروهبندی میکنیم و سپس بر این اساس به اشیاء خاص در جهان اشاره میکنیم. به نظر میرسد که چیواوای همسایه من و سگ لاسی به نوعی اشتراکات زیادی دارند و طبق نظم طبیعی چیزها با هم همراه هستند. به همین ترتیب، به نظر میرسد اشیاء دیگری که در جهان پیدا میکنیم، مانند الکترونها، جداول و اعداد، به طور طبیعی در این گروه قرار نمیگیرند.

بخش زیادی از تحقیقات علمی به دنبال ایجاد تمایزات مناسب برای توضیح پدیدههای خاص یا انجام بهترین پیشبینیهای ممکن است. برای مثال، یک فیزیکدان میتواند به ما اطلاع دهد که نوترونها و الکترونها از انواع متمایزی هستند، اما با توجه به نظریه نسبیت انیشتین، نمیتوان تمایز روشنی بین جنبه مکانی و جنبه زمانی قائل شد. یک گیاهشناس ممکن است طبقهبندیای ایجاد کند که گردو را به عنوان میوه طبقهبندی کند و تلویحاً بگوید که آنها به نوعی بیشتر به سیب نزدیک هستند تا هویج.

در حالی که ما معمولاً، یا در یک زمینه علمی، انواع مرتبط را شناسایی میکنیم و تمایزات مناسبی را ترسیم میکنیم، فیلسوفانی که به متافیزیک میپردازند، تلاش میکنند تا این تمایزات را ترسیم کنند و انواعی را که اساسیترین یا بنیادیترین انواع واقعیت هستند، شناسایی کنند. درست مانند دانشمندان، متافیزیکدانان نیز مدلهایی را توسعه میدهند. با این حال، اینها مختص هیچ حوزه خاصی از تحقیق نیستند، بلکه به همه حوزههای ممکن مربوط میشوند و از عمومیترین ماهیت برخوردارند و هدفشان توصیف جهان به عنوان یک کل است. برای مثال، فیلسوفان قرن هفدهم، باروخ اسپینوزا، رنه دکارت و گوتفرید ویلهلم لایبنیتس، معتقد بودند که تمام واقعیت از جوهرهایی از انواع مختلف به عنوان حاملان نهایی خواص تشکیل شده است، اگرچه در مورد ماهیت این جوهرها دیدگاههای متفاوتی داشتند. از نظر اسپینوزا، خدا تنها جوهر در سراسر کیهان بود و تمام طبیعت بخشی از این جوهر ابدی، نامتناهی و خود-علت است. با این حال، دکارت معتقد بود که علاوه بر جوهر نامتناهی و الهی، واقعیت خود را به دو نوع دیگر، یعنی ذهن و ماده، تقسیم میکند. از سوی دیگر، لایبنیتس واقعیت را به عنوان مجموعهای بیپایان از ذهنهای بدون امتداد یا جوهرهای ذهنمانند که او آنها را موناد مینامد، تصور میکرد. برای هر سه فیلسوف، متافیزیک تلاشی برای تدوین یک توصیف کلی از جهان است؛ این تلاشی برای یافتن یک نظریه کلی در مورد چگونگی ارتباط چیزها، به معنای وسیع کلمه، با یکدیگر است.

تصور متافیزیکی در این شکل اغلب با استعاره افلاطون از «حکاکی طبیعت در مفاصل آن» مرتبط است. در یونان باستان، فیلسوفان امیدوار بودند دانشی را به دست آورند که به طور جهانی معتبر باشد و با جریان تغییرات روزمره از بین نرود. استراتژی افلاطون این بود که ابتدا خطوط گسل عینی جهان را پیدا کند و مجموعه صحیحی از دسته بندی هایی را که جهان را به شکلی که هست تشکیل می دهند، شناسایی کند. این دسته بندی ها جهان را به روشی که مفاصل یک اسکلت، استخوان ها را از هم جدا می کنند، تقسیم می کنند. تنها با در اختیار داشتن این دسته بندی ها می توانیم گزاره های جهان شمول و درست در مورد واقعیت را تدوین کنیم. در اصطلاحات معاصر، این پروژه اغلب به عنوان جستجوی ساختار متافیزیکی بنیادی واقعیت توصیف می شود – چارچوبی از مفاصل، انواع و الگوهایی که به بهترین شکل، چگونگی جهان را مستقل از نحوه تفکر یا صحبت ما در مورد آن، به تصویر می کشد (به عنوان مثال، به Sider، 2011، فصل 1 مراجعه کنید).

When we ordinarily encounter the world, we find it to be pre-divided into different objects of various pre-given kinds. For instance, we find the world to consist of living and non-living things. Looking more closely at the realm of living things, we find that some living things are in certain respects more similar to one another than they are to other organisms, such as in their appearance, behaviour, or genetic code. Instinctively, we group these beings by introducing certain categories in our language, such as ‘dog’, and then refer to particular objects in the world accordingly. It appears that in some way my neighbour’s chihuahua and the dog Lassie have a lot in common and go together by the natural order of things. Likewise, it seems that other objects we find in the world, such as electrons, tables and numbers, naturally do not belong in this group.

Much of scientific research is engaged in drawing proper distinctions to explain certain phenomena or to make the best possible predictions. A physicist can, for instance, inform us that neutrons and electrons are of distinct kinds, but that a clear-cut distinction between the spatial and the temporal cannot be made in light of Einstein’s theory of relativity. A botanist might develop a taxonomy that classifies walnuts as fruits and imply that they are in some way more closely related to apples than to carrots.

While we ordinarily, or in a scientific context, identify relevant kinds and draw appropriate distinctions, philosophers who engage in metaphysics attempt to draw those distinctions and identify those kinds that are the most basic or fundamental to reality. Just like scientists, metaphysicians develop models. These are not, however, specific to any particular domain of inquiry but concern all possible domains and are of the most general nature, aiming to describe the universe as a whole. For example, the seventeenth-century philosophers Baruch Spinoza, René Descartes, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz believed that all of reality consists of substances of various kinds as ultimate bearers of properties, though they differed in their views about the nature of these substances. For Spinoza, God was the only substance throughout the cosmos, and all of nature is part of this eternal, infinite, self-caused one. Descartes, however, believed that in addition to the infinite, divine substance, reality divides itself into two other kinds, namely minds and matter. Leibniz, on the other hand, conceived reality as an endless pool of extensionless minds or mind-like substances that he calls monads. For all three philosophers, metaphysics is an attempt to formulate a general description of the world; it is the quest for a general theory of how things, in the broadest sense of the term, relate to one another.

The metaphysical enterprise conceived in this form is often associated with Plato’s metaphor of ‘carving nature at its joints’. In ancient Greece, philosophers hoped to secure knowledge that holds universally and would not be swept away by the flux of everyday change. Plato’s strategy was to locate the objective fault lines of the world first, identifying the correct set of categories that make up the world as it is. These categories divide the world in the way that joints of a skeleton divide bones. Only by having these categories at our disposal can we formulate universally true statements about reality. In contemporary terms, this project is often described as the search for the fundamental metaphysical structure of reality—a framework of joints, kinds, and patterns that best captures how the world is independently of how we think or talk about it (see, e.g., Sider, 2011, ch. 1).

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

Download: Cognitive Metaphysics

نظرات کاربران