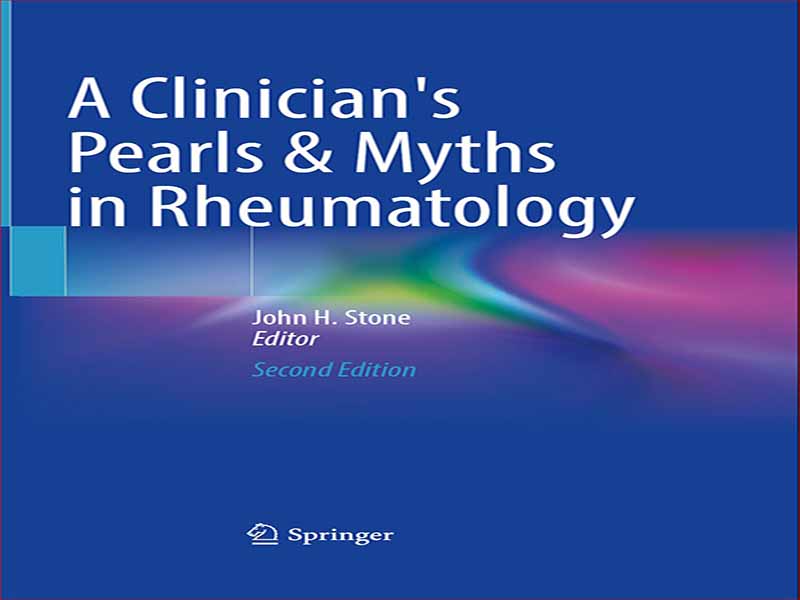

- عنوان کتاب: A Clinician’s Pearls & Myths in Rheumatology

- نویسنده: John H. Stone

- حوزه: روماتولوژی

- سال انتشار: 2023

- تعداد صفحه: 763

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 33.1 مگابایت

وقتی کودکی در کلاس دوم بودم، مادرم انگشت اشارهای به شدت دردناک روی دست راستش پیدا کرد. پس از چندین شب بی خوابی با درد بی امان که از من پنهان شده بود، در بیمارستان بستری شد. جراح به تومور گلوموس مشکوک شد – یک رشد خوش خیم که گاهی در بستر ناخن ایجاد می شود. اما هیچ توموری در جراحی یافت نشد. در عوض، جراح مشاهدات شگفتانگیزی را با پدرم در میان گذاشت: «وقتی ناخن او را برداشتم، خونریزی نداشت.» و در آن لحظه، ماهیت بیماری او برای پزشکان او و پدرم که خود یک پزشک بود آشکار شد. مادرم در نوجوانی پدیده رینود را توسعه داده بود. وقتی او و پدرم تازه ازدواج کرده بودند و او دانشجوی پزشکی بود، از عجیب و غریب انگشتان سفید رنگ پریده او که گاهی اوقات حتی در تابستان رشد می کرد، با هم فکر می کردند. در حدود زمانی که من به دنیا آمدم، او از یک مشکل پوستی رنج می برد که سال ها بعد فهمیدم که درماتیت هرپتی فرمیس است. به عنوان یک پسر جوان، به یاد می آورم که او پاهایش را که به شدت خارش دارند می خراشید. همانطور که بزرگ شدم، متوجه زخم های ظریفی شدم که روی صورت او باقی مانده بود، که معمولاً با آرایش به خوبی پنهان می شد. التهاب فعال پوست پس از چند سال محو شد، اما سایر جنبههای کالیدوسکوپ خودایمنی مورد توجه دقیقتری قرار گرفتند. انگشت ایسکمیک در زمینه مسائل قبلی او منجر به تشخیص اسکلرودرمی شد. در این پرتو، بیشتر وقایع پزشکی در زندگی مادرم اکنون معنادار است. انگشت او در جراحی به دلیل شدت انقباض عروق خونریزی نکرده بود. شکل انگشتان او که هنوز هم می توانم ببینم و به یاد دارم، از جمله ناخن خمیده ای که هرگز به حالت عادی رشد نکرد، نتیجه بیماری او بود. کلسینوزها و حفره های دیجیتالی که در انگشتان او ایجاد شد نیز پیامدهای بیماری کند اما بی امان او بود، و همچنین حملات متناوب دیسفاژی ناشی از اختلال حرکت مری. برای مدتی، در دوران نوجوانی من، مادرم اغلب مجبور بود خود را از سر میز شام معاف کند، زیرا نمی توانست غذایش را ببلعد. خاطره ای دردناک برای من علیرغم آن، مامان زندگی کاملی داشت و به نظر اکثریت این بود که هیچ چیز او را کند نمی کند: بزرگ کردن دو پسر پرخاشگر. همسری دوست داشتنی بودن و بازگشت به تحصیلات تکمیلی؛ تبدیل شدن به یک معلم فداکار کلاس اول؛ با وجود انگشتان حساس در خیاطی، بافندگی، آشپزی و نواختن پیانو، مدام از دستانش استفاده می کند. لذت بردن از دوستان مادام العمر ؛ حضور در بازی های فوتبال ما با دستکش برای مقابله با حملات رینود؛ و لذت بردن از سفرهای خانوادگی. همه چیز خیلی زود متوقف شد. زمانی که کارآموز پزشکی بودم، اپراتور بیمارستان به من پیج میکرد تا با پدرم تماس بگیرم. مادر به دلیل اسکلرودرمی روده دچار انسداد حاد روده شده بود و همان روز صبح به عمل جراحی برده شده بود. من به خانه پرواز کردم، کنار بالین او در بخش مراقبت های ویژه. در آنجا، بسیار شکنندهتر از آنچه که هر کسی متوجه شده بود، دوازده روز بعد به دلیل سندرم دیسترس تنفسی بزرگسالان درگذشت. البته علت واقعی اسکلرودرما بود. او 54 ساله بود. تسلیت اندکی است که حوادث سلامتی آسیب زا در خانواده یک پزشک را به پزشک بهتری تبدیل می کند. با این حال درست است. مبارزه تقریباً مادام العمر مادرم با اسکلرودرمی – که از قضا “محدود” در نظر گرفته می شود – به من کمک می کند تا عدم قطعیت ها، ناامیدی ها و اشک های بیمارانم و خانواده هایشان را درک کنم. البته بیماری مادر به روماتولوژیست شدن من کمک کرد و کارم را وقف کمک به بیمارانی برای رسیدگی به بیماری هایی مانند او کردم. پس مناسب است که این کتاب به او تقدیم شود.

When I was a child in the second grade, my mother developed an acutely painful index finger on her right hand. After several sleepless nights with unrelenting pain that was disguised from me, she was admitted to the hospital. The surgeon suspected a glomus tumor—a benign growth that sometimes develops in the nailbed. But no tumor was found at surgery. Instead, the surgeon shared an astonishing observation with my father: “When I removed her fingernail, she didn’t bleed.” And at that point, the nature of her disease began to dawn on her doctors and on my father, who was himself a physician. My mother had developed Raynaud’s phenomenon as a teenager. When she and my father were newlyweds and he was a medical student, they had mused together at the oddity of her intermittently pale white fingers, which developed sometimes even in the summer. Around the time I was born, she suffered from a skin problem that I learned—years later—was dermatitis herpetiformis. As a young boy, I remember her scratching her intensely itchy legs. As I grew up, I became aware of the subtle scars left on her face, usually well-hidden with makeup. The active skin inflammation faded after a few years, but other aspects of the autoimmune kaleidoscope came into sharper focus. The ischemic finger in the context of her preceding issues led to the diagnosis of scleroderma. In that light, most of the medical events in my mother’s life make sense now. Her finger hadn’t bled at surgery because of the severity of vasoconstriction. The shapes of her fingers that I can still see and remember dearly, including the curved fingernail that never grew back normally, were the result of her disease. The calcinoses and digital pitting that developed in her fingers were also consequences of her slowmoving but relentless illness, as were the intermittent bouts of dysphagia caused by esophageal dysmotility. For a time, during my teens, my mother often had to excuse herself from the dinner table because she just couldn’t swallow her food. A painful memory for me. Despite that, Mom led a full life and it seemed to most that nothing slowed her down: raising two rambunctious boys; being a loving wife and returning to graduate school; becoming a devoted first-grade teacher; using her hands constantly in spite of sensitive fingers on sewing, knitting, cooking, and playing the piano; enjoying lifelong friends; attending our soccer games with mittens on to counter Raynaud’s attacks; and delighting in family travel. It all came to a halt far too early. When I was a medical intern, the hospital operator paged me to return a call from my father. Mom had developed an acute bowel obstruction because of scleroderma gut and had been taken to surgery that morning. I flew home, to her bedside in the intensive care unit. There, far more fragile that anyone had realized, she died twelve days later of adult respiratory distress syndrome. The real cause, of course, was scleroderma. She was 54 years old. It is little consolation that traumatic health events in one’s family make a physician a better doctor. Yet it is true. My mother’s nearly lifelong struggle with scleroderma—ironically regarded as “limited”—helps me understand the uncertainties, frustrations, and tears of my patients and their families. Mom’s illness, of course, contributed to my becoming a rheumatologist and dedicating my career to helping patients address diseases like hers. It is only fitting, then, that this book is dedicated to her.

این کتاب را میتوانید بصورت رایگان از لینک زیر دانلود نمایید.

نظرات کاربران