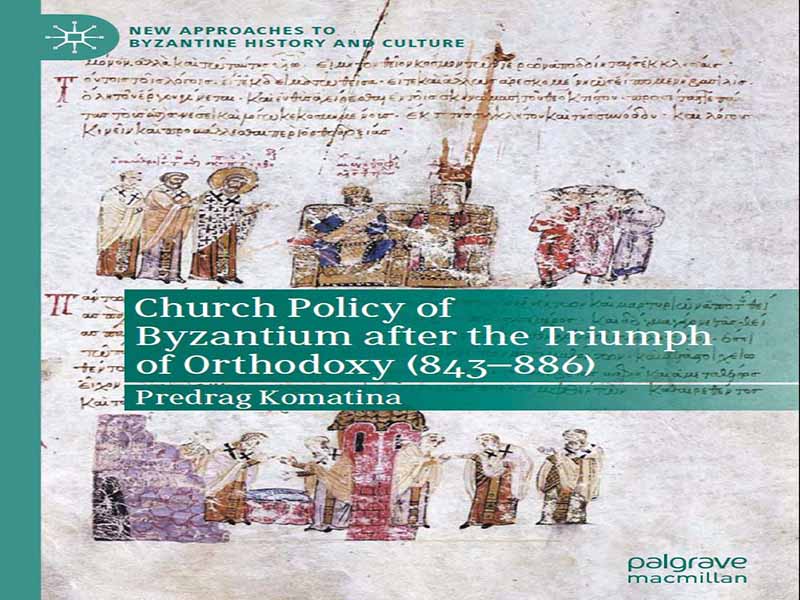

- عنوان کتاب: Church Policy of Byzantium after the Triumph of Orthodoxy

- نویسنده: Predrag Komatina

- حوزه: مسیحیت

- سال انتشار: 2025

- تعداد صفحه: 514

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 4.14 مگابایت

مونوگراف «سیاست کلیسای بیزانس پس از پیروزی ارتدکس (۸۴۳-۸۸۶)» نسخهی اصلاحشده و بازنگریشدهی نسخهی صربی «سیاست کلیسای بیزانس پس از پیروزی ارتدکسها» است که در سال ۲۰۱۴ منتشر شد. این کتاب نیز بر اساس رسالهی دکترای «سیاست کلیسای بیزانس پس از پیروزی ارتدکسها» نوشته شده است. این رساله در سال ۲۰۱۲ در دانشکدهی فلسفهی دانشگاه بلگراد، در حضور یک کمیسیون بینالمللی متشکل از پروفسور دکتر ولادا استانکوویچ، استاد راهنما، پروفسور دکتر رادیووی رادیچ، استاد فلسفهی دانشگاه بلگراد، پروفسور دکتر آنجل نیکولوف، استاد فلسفهی دانشگاه سنت کلمنت اوهرید، صوفیه، پروفسور دکتر تاتیانا سوبوتین-گلوبوویچ، استاد فلسفهی دانشگاه بلگراد، ارائه شد. عبارت «سیاست کلیسای بیزانس» که در عنوان آمده است، باید به «سیاست امپراتوری بیزانس در امور کلیسایی» اشاره داشته باشد، یعنی سیاستی که امپراتور و مقامات امپراتوری نسبت به کلیسا و در حوزه امور کلیسایی به طور کلی اتخاذ میکردند. در دوره مورد نظر، این شامل مسائل مختلف شمایلشکنی و ارتدکس، انتصاب پاتریارخها، روابط با کلیسای روم، اختلافات کلامی با مسلمانان، مسیحیان غیر کالسدونی و فرقههای مسیحی، فعالیتهای تبلیغی در خارج از مرزهای امپراتوری با هدف تغییر دین مردمان خارجی به مسیحیت و همچنین نسبت به اقلیتهای مذهبی داخل آن، و همچنین پتانسیل سیاسی و فکری پشت این سیاستها میشود. تأکید بر این نکته مهم است که این بدان معنا نیست که سیاست کلیسا همیشه یکسان یا حتی ثابت بوده است. این سیاست تا حد زیادی به شخصیت امپراتور یا سایر دارندگان اقتدار عالی دولتی، شخصیت پاتریارخ و شرایط عمومی بستگی داشت و مطابق با این عوامل تغییر میکرد. علاوه بر این، قصد این نیست که بگوییم اقتدار امپراتوری و پدرسالاری باید به عنوان نهادهایی فی نفسه، مستقل از شخصیتهای حاملان آنها، در نظر گرفته شوند. واضح است که رابطه بین این دو پیچیدهتر بوده و از بسیاری جهات به شخص امپراتور یا پدرسالار، به رابطه شخصی و نگرشهای شخصی آنها نسبت به یکدیگر بستگی داشته است. همین امر را میتوان در مورد روابط بین کلیساهای شرقی و غربی نیز گفت که باز هم پیچیده و گاهی به طرز چشمگیری، مطابق با شرایط سیاسی و سایر شرایط تغییر میکرد و باعث میشد که همیشه نتوان از یک سیاست ثابت و پایدار امپراتور نسبت به پاپ، یا پاپ نسبت به پدرسالار یا برعکس، حتی در هنگام برخورد با همان شخصیتهای اصلی، صحبت کرد. همین امر در مورد روابط درون اردوگاه حزب پیروز شمایلپرست در دوره پساشمایلشکنی نیز صادق بود، که نمیتوان آن را به طور دقیق به جناحهای “افراطی” و “میانهرو” تقسیم کرد، همانطور که معمولاً در تحقیقات فرض میشود. بنابراین، «سیاست کلیسای بیزانس» در دوره پساآیکونوکلاستیک به عنوان نوعی پدیده تاریخی ارائه نمیشود، بلکه به عنوان تاریخچهای از وقایعی است که امور کلیسایی بیزانس را در این دوره مشخص کرده است. احیای آیین شمایلپرستی در سال ۸۴۳ به عنوان نقطه شروع در نظر گرفته میشود، زیرا نمایانگر تقاطعی در تاریخ کلیسایی و سیاسی بیزانس بود، زمانی که امپراتوری مسیحی رومیان به ریشههای ارتدکس خود بازگشت. دوره پس از آن با آشفتگی در کلیسای بیزانس، انشعابات بیشتر، زمانی که کهنه، نو را به دنیا آورد و نو، کهنه را به سایه انداخت، مشخص شد، دورهای که در آن دولت سعی در تثبیت کلیسا داشت، اما آشفتگیها در کلیسا اغلب دولت را بیثبات میکرد. علاوه بر این، این دوره همچنین شاهد احیای آموزش سکولار بود، که نمایندگان آن بیش از هر زمان دیگری تلاش میکردند تا مدیریت امور کلیسایی و مهمترین مناصب را از دست رهبانیت سختگیر، غنی از روح، اما کمسواد به دست گیرند. رهبانیت، که تحت آزار و اذیت شمایلشکنان قرار داشت، دوباره به عنوان بزرگترین مرجع اخلاقی در جامعه بیزانس ظهور میکند. در چنین شرایط داخلی، گسترش بیرونی بیسابقهای از کلیسا و مذهب بیزانس رخ داد، از جمله گنجاندن تعداد زیادی از روسهای بربر، خزرها، بلغارها و اسلاوها در اروپای مرکزی در دایره فرهنگی و معنوی بیزانس. ارتدکس بیزانس سپس با موفقیت با چالشهای کلامی اسلام کنار آمد، در حالی که بقای یهودیان را در قلمرو خود تهدید میکرد. سرانجام، در آن دوران، کلیسای قسطنطنیه برای اولین بار سعی کرد کاملاً مستقل از مقام رسولی روم قدیم عمل کند و خود را مرکز کل جهان مسیحی بداند. شخصیتهای اصلی در تمام این وقایع، حاملان بالاترین مقام دولتی بودند – ملکه تئودورا (842-856)، لوگوتته تئوکتیستوس (تا 855)، قیصر بارداس (تا 866)، امپراتور میخائیل سوم (842-867) و امپراتور باسیل اول (867-886). سپس هولد…

The monograph Church Policy of Byzantium after the Triumph of Orthodoxy (843–886) represents an amended and reworked version of the Serbian edition Crkvena politika Vizantije od kraja ikonoborstva do smrti cara Vasilija I, Beograd 2014, which, again, was based on the doctoral dissertation “Crkvena politika Vizantije (843–886)”, defended at the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philosophy in 2012, before an international commission, which consisted of Prof. Dr Vlada Stanković, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philosophy (mentor), Prof. Dr Radivoj Radić, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philosophy, Prof. Dr Angel Nikolov, University “St Clement of Ohrid”, Sofia, Prof. Dr Tatjana Subotin- Golubović, University of Belgrade, Faculty of Philosophy. The phrase “Church policy of Byzantium”, indicated in the title, should be understood to refer to the “policy of the Byzantine Empire in ecclesiastical affairs”, that is the policy that the emperor and the imperial authorities conducted towards the Church and in the field of ecclesiastical affairs more generally. In the period concerned, this covers the various issues of Iconoclasm and Orthodoxy, the appointment of the patriarchs, relations with the Church of Rome, theological disputes with the Muslims, Non- Chalcedonian Christians and Christian sects, missionary activity outside the borders of the Empire aimed at the conversion of foreign peoples to Christianity, as well as towards the religious minorities inside it, but also the political and intellectual potential that stood behind these policies. It is important to emphasize that this does not mean church policy was always the same or even consistent. It depended largely on the personality of the emperor or other holders of supreme state authority, on the personality of the patriarch, and on general circumstances, and shifted in accordance with these factors. Furthermore, it is not the intention to suggest that the imperial and patriarchal authority should be viewed as institutions per se, existing independently of the personalities of their bearers. It is apparent that the relationship between the two was more complex and in many respects depended on the person of the emperor or the patriarch, on their personal relationship and personal attitudes towards one another. The same can be said of relations between the Eastern and Western Churches, which again were complex and changed, sometimes dramatically, in accordance with political and other circumstances making it impossible always to speak of a constant and consistent policy of the emperor towards the pope, or of the pope towards the patriarch or viceversa, even when dealing with the same protagonists. The same was also true for the relationship within the camp of the victorious iconophile party in the post-iconoclastic period, which cannot be viewed as strictly divided into “extremist” and “moderate” factions, as is usually assumed in the scholarship. Thus, the “church policy of Byzantium” in the posticonoclastic period is not presented as a kind of a historical phenomenon, but rather as a history of the events that marked the ecclesiastical affairs of Byzantium in the given period. The restoration of the cult of icons in 843 is taken as a starting point, as it represented a crossroads in both the ecclesiastical and political history of Byzantium, when the Christian Empire of the Romans returned to its Orthodox roots. The period that followed was marked by turbulence in the Byzantine church, further schisms, when the old gave birth to new, and the new threw the old into the shadows, in which the state tried to stabilize the church, but disturbances in the church often destabilized the state. Moreover, the period also witnessed the restoration of secular learning, the representatives of which strove more than ever to take over the management of ecclesiastical affairs and the most important positions from the hands of strict, rich in spirit, but poorly educated monasticism. Monasticism, persecuted under the iconoclasts, re-emerges as the greatest moral authority in Byzantine society. In such internal circumstances, an unprecedented external expansion of the Byzantine church and religion took place, including the inclusion of vast numbers of barbarian Russians, Khazars, Bulgarians and Slavs in Central Europe into the Byzantine cultural and spiritual circle. Byzantine Orthodoxy then successfully coped with the theological challenges of Islam, while threatening the very survival of the Jews in its territory. Finally, in that era, the Church of Constantinople tried for the first time to act completely independently of the Apostolic See of Old Rome and to see itself as the centre of the entire Christian universe. The main protagonists in all those events were the bearers of the highest state authority—Empress Theodora (842–856), Logothete Theoctistus (until 855), Caesar Bardas (until 866), Emperor Michael III (842–867) and Emperor Basil I (867–886); then the holders of the highest ecclesiastical authority—patriarchs of Constantinople Methodius (843–847), Ignatius (847–858, 867–877) and Photius (858–867, 877–886). Nor should we forget intellectuals, such as Constantine the Philosopher († 869) and monks, such as his brother Methodius († 885). This epoch, so rich in events and so important for Byzantine and European history, ended with the disappearance of the last of its protagonists—the death of Methodius and Emperor Basil I and Photius’ final withdrawal from the stage. Those events, in 885 and 886, marked a new turning point in the history of Byzantine church politics, and directed its course in a different direction. The period of Byzantine history between 843 and 886 is fairly well covered by historical sources. As far as narrative sources are concerned, the period this book deals with did not, however, produce any contemporary historians or chroniclers to describe it. The only one writing in the genre at the time was George the Monk, and his Chronicle ends precisely in the year 843, with the events that are taken as the starting point here. Other chroniclers whose works cover the period between 843 and 886 wrote almost a century later, in the middle of the tenth century. These are the Continuator of Theophanes, Genesius, Symeon the Logothete, authors from the so-called groups of Symeon the Logothete and the continuers of George the Monk. However, due to the distance in time from the events they were describing, the statements of these chroniclers are not always the most accurate or precise, sometimes obscured by legend, and often burdened with ideology. Since they were created during the reign of emperors from the Macedonian dynasty, descended from Basil I, on the whole, they portray the reign of Michael III in a negative light.

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

Download: Church Policy of Byzantium after the Triumph of Orthodoxy

نظرات کاربران