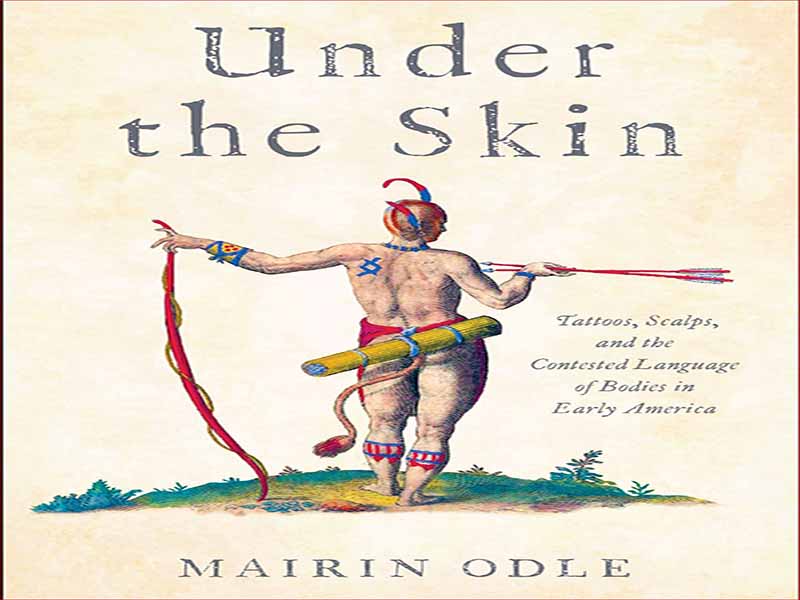

- عنوان کتاب: UNDER THE SKIN / Tattoos, Scalps, and the Contested Language of Bodies in Early America

- نویسنده: Mairin Odle

- حوزه: جامعه شناسی آمریکا

- سال انتشار: 2022

- تعداد صفحه: 177

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 15.0 مگابایت

جان لانگ، تاجر، مترجم و پیشاهنگ گاه به گاه نیروهای بریتانیایی، در سفرها و سفرهای خود در سال 1791 با افتخار ادعا کرد که با جوامع بومی، به ویژه شهر موهاوک Kanehsatà:ke، در نزدیکی مونترال، و جوامع Ojibwe (Anishinabe) در شمال آشنایی دارد. از دریاچه های بزرگ لانگ نوشت، پس از اینکه «هنگ را ترک کرد تا از زندگی هندی مورد علاقهام لذت برد»، برای پیوستن به دهکده موهاک در سواحل دریاچه دو کوه، «در حالی که یک پوست سر را به عنوان غنائم خدمات من حمل میکرد» سفر کرد. 1 اگرچه او برای خوانندگان ناآشنا توضیح داد که پوست سر «شیوهای از شکنجه مخصوص سرخپوستان است» و در حالی که معمولاً کشنده است، «مرگ همیشه اتفاق نمیافتد»، لانگ هیچکدام توضیح نداد که پوست سر از کجا (یا چه کسی) آمده است. و هیچ نگرانی خاصی را در توجیه داشتن آن نشان نداد. در حالی که اسکالپینگ میتواند موجب اتهامات شدید و سرزنشهای خشونتآمیز آمریکاییها و بریتانیاییها شود، ذکر نسبتاً غیرمعمول لانگ همچنین نشان میدهد که این عمل تا چه حد عمیقاً در تصورات انگلیسی-آمریکایی و رویه نظامی جا افتاده است. لانگ در خاطرات خود اظهار داشت که تسلط فرهنگی او به زبانها و شیوههای بومی به یک دگرگونی تجسم یافته گسترش یافته است: «اگر تصادفاً غریبهای در میان ما میآمد (مگر اینکه تصمیم میگرفتم مورد توجه قرار بگیرم)، هیچکس نمیتوانست مرا از هندیها متمایز کند. با این تصور که دقیقاً مانند یک وحشی ظاهر میشوم، گهگاه با قایقرانی به مونترال میرفتم و اغلب بهعنوان یک هندی از پستها عبور میکردم». در حالی که در Pays Plat در دریاچه سوپریور توقف می کرد، توسط یکی از رهبران Ojibwe به نام Madjeckewiss (گاهی اوقات Matchekewis نوشته می شود) به او پیشنهاد فرزندخواندگی داده شد. او پذیرفت: «اگرچه من این مراسم را انجام نداده بودم، اما از ماهیت آن کاملاً بی اطلاع نبودم، زیرا سایر تاجران از درد و رنجی که متحمل شدند مطلع شدم. . . . با این حال، تصمیم گرفتم که تسلیم آن شوم، مبادا امتناع من از افتخاری که برای من در نظر گرفته شده است به دلیل ترس نسبت داده شود، و بنابراین مرا برای احترام به کسانی که انتظار داشتم از آنها مزایای بزرگی کسب کنم و با آنها درگیر بودم، بی ارزش جلوه دهد. برای مدت قابل توجهی ادامه دهید.»3 «دردی» که لانگ به آن اشاره کرد، خالکوبی بود که طی چند روز انجام شد. او این روش را با صدایی جدا و سوم شخص توضیح داد و توضیح داد که یک هنرمند از باروت مخلوط شده با آب برای کشیدن طرحی روی «فردی که باید به فرزندخواندگی میپذیرد استفاده کرد. . . پس از آن، با ده سوزن آغشته به سرخابی و ثابت کردن آن در یک قاب چوبی کوچک، قسمتهای مشخص شده را سوراخ میکند و در جایی که خطوط پررنگتر ظاهر میشود، گوشت را با سنگ چخماق میتراشد.» خالکوبی حاصل قرمز و آبی خواهد بود که نتیجه رنگدانه های باروت و سرخاب است. وقتی خالکوبی کامل شد، لانگ نوشت: «آنها به مهمانی یک نام میدهند. چیزی که به من اختصاص دادند، آمیک یا بیور بود.» (4) توصیف تا حدودی مورب خاطرات مشخص نمیکند که آیا طراحی خالکوبی لانگ با نام جدید او مطابقت دارد یا حتی این روند به همان اندازه که او پیشبینی کرده بود دردناک بود. اما معلوم است که آن را افتخار می دانست. او همچنین آن را بهعنوان یک مبادله، دریافت یک منفعت ملموس مینگریست که با هدیه «چاقوی پوست سر، ماهی تاماهاوک، سرخابی» و سایر کالاها به Madjeckewiss و بقیه جامعه «بازگشت برای آن» انجام داد. غیر معمول، اما او تنها نبود. بسیاری دیگر در آمریکا اولیه ظاهر فیزیکی داشتند که در نتیجه تعامل با افراد جدید و ناآشنا تغییر کرده بود. چنین افرادی گوشت مشخص خود را کانون واکنشهایی میدانستند که از کنجکاوی یا همدردی گرفته تا بدگمانی یا حتی تنفر را شامل میشود. این اجساد اولیه آمریکایی، چه شکنجه شده باشند و چه تزئین شده، با خشونت و یا از نزدیک نشانه گذاری شده باشند، آرشیوهای غنی و نگران کننده ای از تجربیات بشر بودند. برخی دیگر از نمادهای مرتبط با چنین نشانهها و بدنههای مشخص شده برای اهداف نظامی، سیاسی یا فرهنگی خود استفاده کردند. در سرتاسر آمریکای شمالی قرن هفدهم و هجدهم، رقابتهای قدرت تأثیر محسوسی بر بدن تازهواردها و بومیان گذاشت و شواهد فیزیکی به دقت مورد بررسی قرار گرفت.

John Long, a trader, interpreter, and occasional scout for British forces, proudly claimed in his 1791 Voyages and Travels an expert familiarity with Native societies, particularly the Mohawk town of Kanehsatà:ke, near Montreal, and the Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) communities north of the Great Lakes. Having “quitted the regiment to enjoy my favorite Indian life,” Long wrote, he traveled to join the Mohawk village on the shores of Lake of Two Mountains, “carrying a scalp as a trophy of my services.” 1 Although he explained, for unfamiliar readers, that scalping was “a mode of torture peculiar to the Indians” and that while usually fatal, “death does not always ensue,” Long neither accounted for where (or whom) the scalp had come from nor indicated any particular concern in justifying his possession of it. While scalping could prompt heated accusations and violent recriminations from both Americans and Britons, the relatively casual mention by Long also demonstrates how deeply embedded the practice had become in Anglo-American imaginations and military procedure. In his memoirs, Long asserted that his cultural fluency with Native languages and practices extended into an embodied transformation: “If accidentally a stranger came among us (unless I chose to be noticed), no one could distinguish me from the Indians. Presuming on my appearing exactly like a savage, I occasionally went down in a canoe to Montreal, and frequently passed the posts as an Indian.”2 In 1777, he took a job as interpreter for a trade expedition north of the Great Lakes, and while stopping over in Pays Plat on Lake Superior, was offered adoption by an Ojibwe leader named Madjeckewiss (sometimes spelled Matchekewis). He accepted: “Though I had not undergone this ceremony, I was not entirely ignorant of the nature of it, having been informed by other traders of the pain they endured. . . . I determined, however, to submit to it, lest my refusal of the honor intended me should be attributed to fear, and so render me unworthy of the esteem of those from whom I expected to derive great advantages, and with whom I had engaged to continue for a considerable time.”3 The “pain” to which Long referred was a tattooing that took place over several days. He described the procedure in a detached, third-person voice, explaining that an artist used gunpowder mixed with water to draw a design on “the person to be adopted . . . after which, with ten needles dipped in vermilion, and fixed in a small wooden frame, he pricks the delineated parts, and where the bolder outlines occur he incises the flesh with a gun-flint.” The resulting tattoo would be red and blue, a result of the gunpowder and vermilion pigments. When the tattoo was complete, Long wrote, “they give the party a name; that which they allotted to me, was Amik, or Beaver.”4 The memoir’s somewhat oblique description leaves unclear whether the design of Long’s tattoo corresponded with his new name or even whether the process was as painful as he had anticipated. But it is clear that he regarded it as an honor. He also viewed it as an exchange, the receipt of a tangible benefit that he made “return for” in gifts of “scalping-knives, tomahawks, vermilion” and other goods to Madjeckewiss and the rest of the community.5 Long may have been unusual, but he was not alone. Many others in early America had physical appearances that had been altered as a result of interactions with new and unfamiliar people. Such individuals found their marked flesh the focus of reactions ranging from curiosity or sympathy to suspicion or even revulsion. Whether tortured or ornamented, violently or intimately marked, these early American bodies were rich and troubling archives of human experience. Others used the symbolism associated with such marks, and such marked bodies, for their own military, political, or cultural purposes. Across seventeenth-and eighteenth-century North America, contests for power took tangible effect on the bodies of newcomers and Natives alike, and that corporeal evidence was closely scrutinized.

این کتاب را میتوانید از لینک زیر بصورت رایگان دانلود کنید:

Download: UNDER THE SKIN / Tattoos, Scalps, and the Contested Language of Bodies in Early America

نظرات کاربران