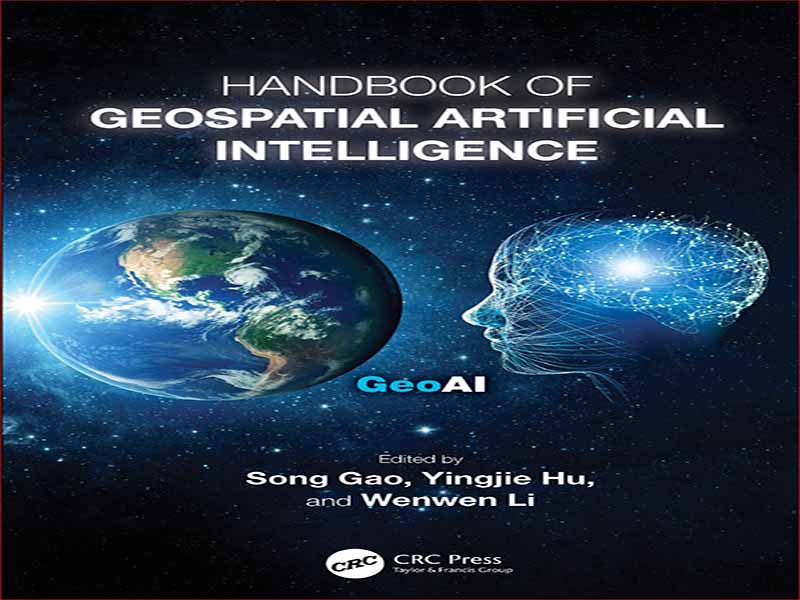

- عنوان کتاب: Handbook of Geospatial Artificial Intelligence

- نویسنده: Song Gao

- حوزه: کاربرد هوش مصنوعی در فضا

- سال انتشار: 2024

- تعداد صفحه: 469

- زبان اصلی: انگلیسی

- نوع فایل: pdf

- حجم فایل: 5.79 مگابایت

برای من افتخار بزرگی است که از من خواسته می شود پیشگفتار این کتابچه راهنمای هوش مصنوعی زمین فضایی را ارائه دهم. GeoAI به سرعت به موضوع اصلی تحقیق و توسعه جدید در جغرافیا، علم اطلاعات جغرافیایی (GI-Science) و در بسیاری از رشتههایی که خود را با الگوها و فرآیندهای پیچیدهای که در حوزه جغرافیایی یافت میشود، تبدیل کرده است. سطح و نزدیک به سطح زمین است). برای این سگ پیر، نه تنها مجموعهای از ترفندهای جدید هیجانانگیز را نشان میدهد، بلکه نشاندهنده تجدید قوا در زمینه قدیمی علوم جغرافیایی در جهتهایی است که اساساً با آنچه قبلاً آمده متفاوت است. از طوفان کاملی از روندها سود می برد: در دسترس بودن بسیاری از منابع جدید داده، از سنجش از راه دور، رسانه های اجتماعی، و شبکه های حسگر. دسترسی به منابع تقریبا نامحدود قدرت محاسباتی؛ و ظهور روش های جدید قدرتمند تجزیه و تحلیل داده ها و یادگیری ماشین. اساساً، GeoAI منعکس کننده یک تغییر اساسی در رویکرد ما برای درک حوزه جغرافیایی است. نیم قرن پیش، علوم جغرافیایی خود را از علوم ارشد فیزیک و شیمی در جستجوی اصول جهانی الگوبرداری کردند (Bunge, 1966). این اصول باید در همه جا و همیشه اعمال شوند، درست مانند جدول تناوبی عناصر مندلیف. آنها همچنین باید ساده باشند، مطابق با اصل معروف به تیغ Occam: وقتی دو فرضیه ممکن است یک پدیده را توضیح دهند، باید سادهتر را اتخاذ کرد. استفاده از قانون گرانش نیوتن برای توضیح اینکه چگونه ارتباطات انسانی با افزایش فاصله کاهش می یابد، مثالی عالی ارائه می دهد و منجر به تحقیقات گسترده در مورد مدل سازی تعامل اجتماعی شد. این واقعیت که چنین مدلهایی هرگز تناسب کامل با دادههای جغرافیایی واقعی را فراهم نمیکنند، ناخوشایند بود، اما با این وجود تخمینهای آنها برای استفاده در بسیاری از برنامهها مناسب بود. علاوه بر این، مدلها هنجار یا استانداردی را ارائه کردند که در شناسایی استثناها، ناهنجاریها و موارد خاص مفید خواهد بود. با این حال، در اواسط دهه 1980، این تلاش برای دنبال کردن علوم جغرافیایی با تقلید از فیزیک مسیر خود را طی کرد. جهان جغرافیایی به وضوح برای مجموعه ای از توضیحات مکانیکی بیش از حد پیچیده بود، و اگر بخواهیم الگوها را کشف کنیم و فرآیندها را شناسایی کنیم، به تکنیک های قوی تری نیاز است. برخی تکنیکهایی را دنبال کردند که با اتخاذ روشهایی که ما آن را روشهای مکانمحور مینامیم، جهانشمولی را کنار گذاشتند، که به تبیینها اجازه میدهد در مکان یا زمان، یا هر دو متفاوت باشند (به عنوان مثال، رگرسیون وزندار جغرافیایی؛ فاثرینگهام، برانسون، و چارلتون، 2002). دیگران شروع به ساخت موتورهای تجزیه و تحلیل کردند که به جای چند فرضیه تعریف شده محدود، مجموعه کاملی از مدل ها را بررسی می کرد. برای مثال اوپنشاو مجموعهای از ماشینهای تحلیل جغرافیایی را ساخت که به دادهها نقش فزایندهای در هدایت فرآیند انتخاب مدل میدهند. خیلی بعد، این رویکرد در اصل پارادایم چهارم، “اجازه دهید داده ها خودشان صحبت کنند” گنجانده شد (هی، تانسلی و تول، 2009). اوپنشاو اولین استفاده کننده از اصطلاح هوش مصنوعی بود و ایده های او در کتابی با عنوان مناسب اما پیشگو جمع آوری شد که اندکی قبل از شروع قرن منتشر شد (Openshaw and Openshaw, 1997). به همین ترتیب، دابسون شروع به نوشتن در مورد آنچه او جغرافیای خودکار نامید (دابسون، 1983) کرد. هم او و هم Openshaw استدلال کردند که کامپیوتر باید به طور فزاینده ای درگیر فرآیند تحقیق شود. چندین دهه بعد این ایده ها در حال ورود به جریان اصلی علوم جغرافیایی هستند، اما با یک تفاوت مهم. در حالی که دابسون و اوپنشاو هر دو در تکنیک های دامنه خاص تحلیل جغرافیایی آموزش دیده بودند، روش های امروزی یادگیری ماشین از هیچ علم حوزه خاصی استفاده نمی کنند، اما در عوض رویکردهای اساسی را به کار می برند که اساساً هر موضوعی که باشند یکسان هستند. بنابراین یکی از ضروریترین نیازها در GeoAI، تکنیکهایی است که اصول کلی را که میدانیم در حوزه جغرافیایی صادق هستند را در بر میگیرد: وابستگی فضایی، ناهمگنی فضایی، مقیاسبندی و غیره. اما در حالی که ممکن است خنثی به نظر برسند، به همان اندازه در هر حوزه ای کاربرد دارند، تکنیک هایی مانند شبکه های عصبی و توسعه جدیدتر آنها مانند DCNN (شبکه های عصبی کانولوشنال عمیق) ممکن است تا حدی از ایده های ابتدایی در مورد عملکرد مغز و مغز انسان تقلید کنند. جستجوی غریزی آن برای الگوها. به نظر می رسد تا حدودی طعنه آمیز است که در رد مدل های مکانیکی ساده فیزیک کلاسیک، ما به دنیای بسیار پیچیده تر اما مکانیکی مشابه شبکه های عصبی جذب شده ایم. علاوه بر این، همانطور که برخی از فصول این مجموعه نشان می دهد، استفاده از DCNN برای تجزیه و تحلیل تصاویر به صراحت مفهوم جغرافیایی وابستگی فضایی یا همان چیزی را که ما به عنوان قانون اول جغرافیای توبلر می شناسیم، فرا می خواند.

It’s a great honor for me to be asked to contribute a foreword to this Handbook of Geospatial Artificial Intelligence. GeoAI has very quickly become a major topic of new research and development in geography, geographic information science (GI- Science), and in many of the disciplines that concern themselves with the complex patterns and processes that can be found in the geographic domain (that is, the sur- face and near-surface of the Earth). To this old dog, it represents not only an exciting set of new tricks, but a reinvigoration of the old field of geographic science in di- rections that are fundamentally different from what came before. It benefits from a perfect storm of trends: the availability of many new sources of data, from remote sensing, social media, and sensor networks; access to almost unlimited resources of computational power; and the emergence of powerful new methods of data analysis and machine learning. More fundamentally, GeoAI reflects a radical shift in our approach to under- standing the geographic domain. Half a century ago the geographic sciences modeled themselves on the senior sciences of physics and chemistry in searching for universal principles (Bunge, 1966). These principles should apply everywhere and at all times, just like Mendeleev’s periodic table of the elements. They should also be simple, in accordance with the principle known as Occam’s Razor: when two hypotheses might explain the same phenomenon, one should adopt the simpler. The use of Newton’s law of gravitation to explain how human communications tend to diminish with in- creasing distance provides an excellent example, and led to extensive research on the modeling of social interaction. The fact that such models will never provide perfect fits to actual geographic data was inconvenient, but their estimates were nevertheless fit for use in a host of applications. Moreover, the models provided a norm or stan- dard that would be helpful in identifying exceptions, anomalies, and special cases. By the mid-1980s, however, this attempt to pursue geographic science by emu- lating physics had run its course. The geographic world was clearly too complex for a set of mechanistic explanations, and more powerful techniques would be needed if we were to discover patterns and identify processes. Some pursued techniques that abandoned universality by adopting what we have come to call place-based meth- ods, which allow explanations to vary across space or time, or both (e.g., Geograph- ically Weighted Regression; Fotheringham, Brunsdon, and Charlton, 2002). Others began to build analysis engines that would explore entire sets of models rather than a few narrowly defined hypotheses. Openshaw, for example, built a series of what he termed geographical analysis machines that would give the data an increasing role in driving the model selection process; much later this approach became enshrined in the principle of the Fourth Paradigm, “Let the data speak for themselves” (Hey, Tans- ley, and Tolle, 2009). Openshaw was an early user of the term artificial intelligence, and his ideas were collected in an appropriately titled but prescient book that was published shortly before the turn of the century (Openshaw and Openshaw, 1997). In a similar vein, Dobson began writing about what he called automated geography (Dobson, 1983); both he and Openshaw argued that the computer should become increasingly engaged in the research process. Several decades later these ideas are entering the mainstream of the geographic sciences, but with an important difference. While both Dobson and Openshaw were trained in the domain-specific techniques of geographic analysis, today’s methods of machine learning draw from no particular domain science, but instead apply basic approaches that are essentially the same whatever the subject matter. Thus one of the most urgent needs in GeoAI is for techniques that incorporate the general principles that we know to be true of the geographic domain: spatial dependence, spatial het- erogeneity, scaling, etc. But while they may appear to be neutral, applying equally well to any domain, techniques such as neural networks and their more recent devel- opments such as DCNN (deep convolutional neural networks) may to some extent emulate rudimentary ideas about the workings of the human brain and its instinctive search for patterns. It seems somewhat ironic that in rejecting the simple mechanistic models of classical physics, we have gravitated to the vastly more complex but sim- ilarly mechanistic world of neural networks. Moreover, as some of the chapters of this collection show, the use of DCNN to analyze imagery explicitly invokes the geo- graphic concept of spatial dependence, or what we know familiarly as Tobler’s First Law of Geography.

این کتاب را میتوانید بصورت رایگان از لینک زیر دانلود نمایید.

نظرات کاربران